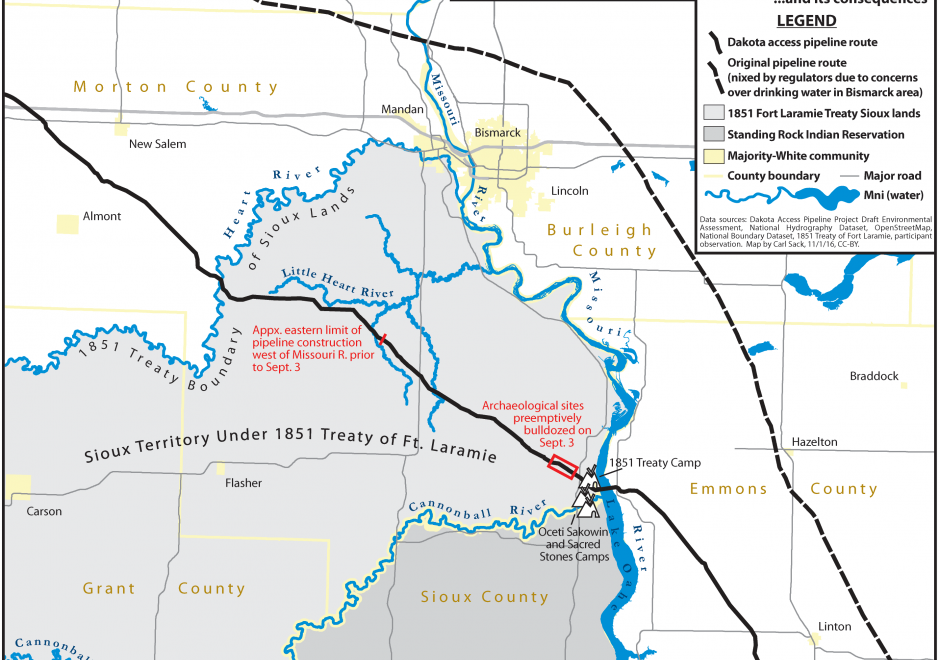

CV-26 - Cartography and Power

Over twenty five years ago, Brian Harley (1989, p. 2) implored cartographers to “search for the social forces that have structured cartography and to locate the presence of power – and its effects – in all map knowledge.” In the intervening years, while Harley has become a bit of a touchstone for citational practices acknowledging critical cartography (Edney, 2015), both theoretical understandings of power as well as the tools and technologies that go into cartographic production have changed drastically. This entry charts some of the many ways that power may be understood to manifest within and through maps and mapmaking practices. To do so, after briefly situating work on cartography and power historically, it presents six critiques of cartography and power in the form of dialectics. First, building from Harley’s earlier work, it defines a deconstructivist approach to mapping and places it in contrast to hermeneutic phenomenological approaches. Second, it places state-sanctioned practices of mapping against participatory and counter-mapping ones. Third, epistemological understanding of maps and their affects are explored through the dialectic of the map as a static object versus more processual, ontogenetic understandings of maps. Finally, the chapter concludes by suggesting the incomplete, heuristic nature of both the approaches and ideas explored here as well as the practices of critical cartography itself. Additional resources for cartographers and GIScientists seeking to further explore critical approaches to maps are provided.

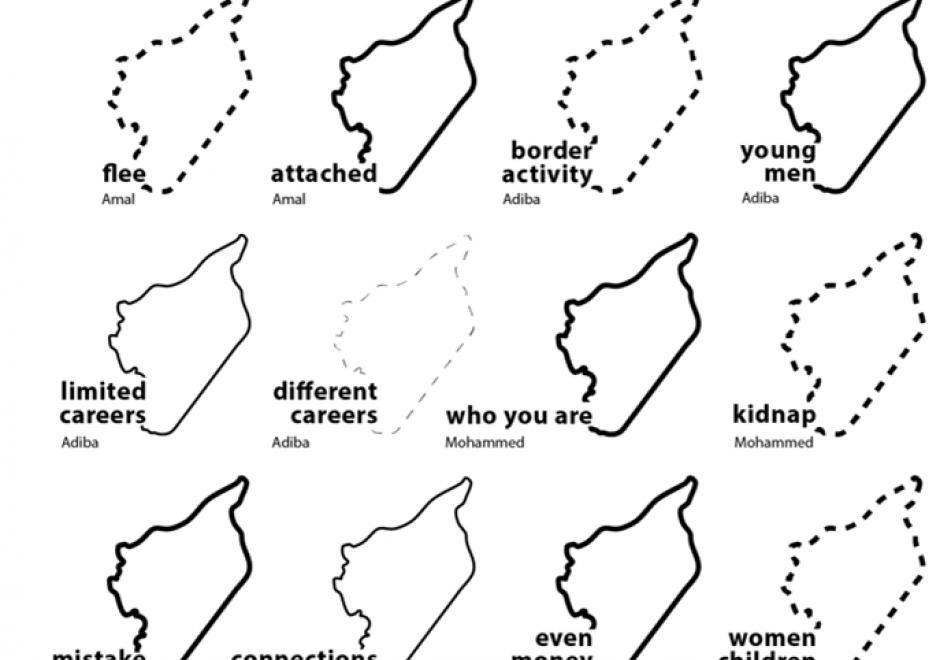

CV-33 - Narrative and Storytelling

Maps are powerful storytellers. Maps have a long history combining spatial relations with cartographic language to locate, analyze, ground, and express stories told across time and space. Today, “story maps” are increasingly visible in cartography, GIScience, digital humanities, data visualization, and journalism due to the volume of available data and increasingly accessible mapping tools. Perhaps, most importantly, maps present world views and much larger (often hidden) stories or “meta-narratives.” These underlying stories often emerge from dominant perspectives that are deeply informed by power structures like racism, patriarchy, ableism, etc. and further generate uneven geographies. Attention to power in narrative and storytelling reveals and gives voice to alternative storylines and perspectives that can be woven together across time and space. In this entry, I introduce multiple conceptualizations of maps and stories from cartography and data journalism to feminist mapping, Black geographies, and decolonial mapping to illustrate the power of narrative and storytelling in mapping. I argue that understanding the power of narrative and storytelling in mapping is an essential skillset for students and professionals alike.