FC-30 - Private sector origins

- Identify some of the key commercial activities that provided an impetus for the development of GIS&T

- Differentiate the dominant industries using geospatial technologies during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s

- Describe the contributions of McHarg and other practitioners in developing geographic analysis methods later incorporated into GIS

- Evaluate the correspondence between advances in hardware and operating system technology and changes in GIS software

- Describe the influence of evolving computer hardware and of private sector hardware firms such as IBM on the emerging GIS software industry

- Discuss the emergence of the GIS software industry in terms of technology evolution and markets served by firms such as ESRI, Intergraph, and ERDAS

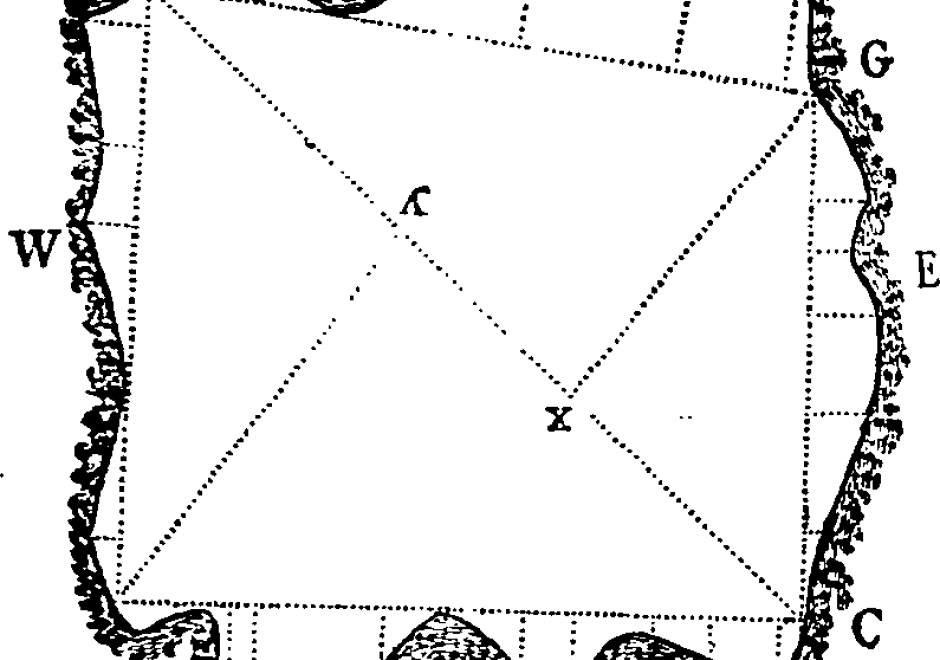

AM-27 - Principles of semi-variogram construction