CP-12 - Location-Based Services

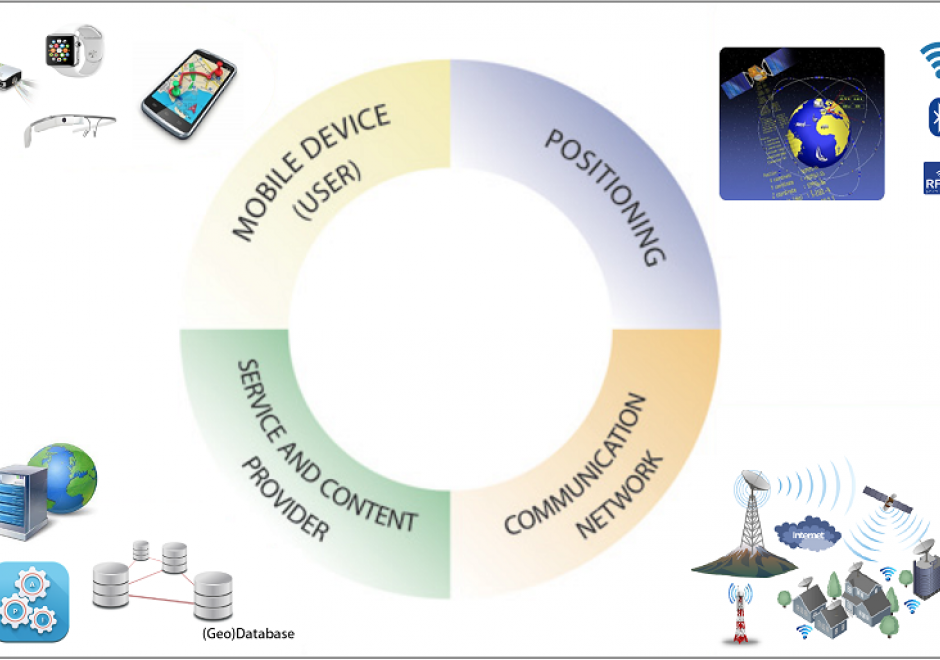

Location-Based Services (LBS) are mobile applications that provide information depending on the location of the user. To make LBS work, different system components are needed, i.e., mobile devices, positioning, communication networks, and service and content provider. Almost every LBS application needs several key elements to handle the main tasks of positioning, data modeling, and information communication. With the rapid advances in mobile information technologies, LBS have become ubiquitous in our daily lives with many application fields, such as navigation and routing, social networking, entertainment, and healthcare. Several challenges also exist in the domain of LBS, among which privacy is a primary one. This topic introduces the key components and technologies, modeling, communication, applications, and the challenges of LBS.

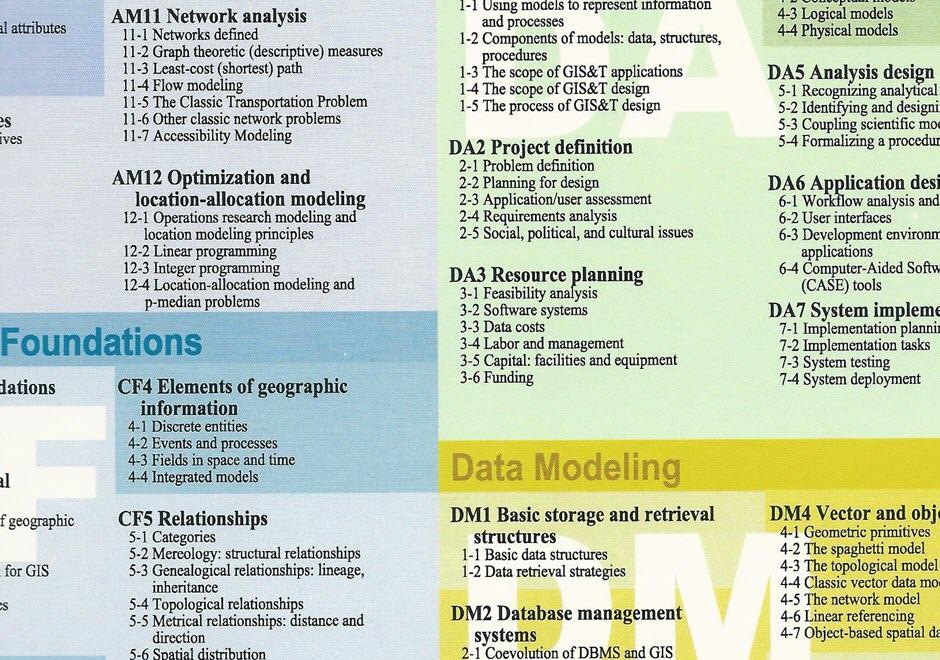

AM-46 - Location-allocation modeling

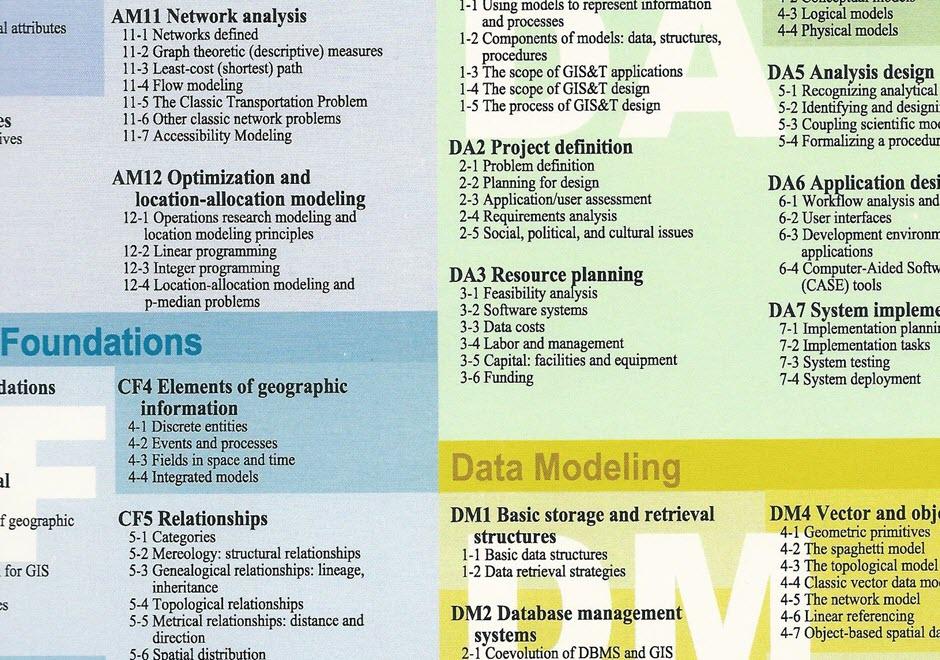

Location-allocation models involve two principal elements: 1) multiple facility location; and 2) the allocation of the services or products provided by those facilities to places of demand. Such models are used in the design of logistic systems like supply chains, especially warehouse and factory location, as well as in the location of public services. Public service location models involve objectives that often maximize access and levels of service, while private sector applications usually attempt to minimize cost. Such models are often hard to solve and involve the use of integer-linear programming software or sophisticated heuristics. Some models can be solved with functionality provided in GIS packages and other models are applied, loosely coupled, with GIS. We provide a short description of formulating two different models as well as discuss how they are solved.