FC-02 - Epistemology

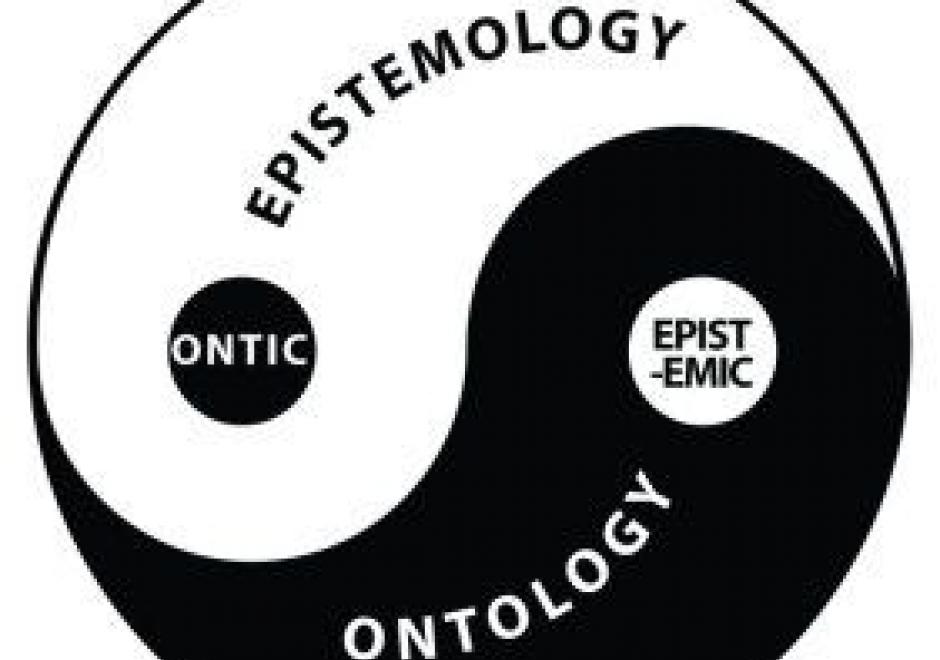

Epistemology is the lens through which we view reality. Different epistemologies interpret the earth and patterns on its surface differently. In effect, epistemology is a belief system about the nature of reality that, in turn, structures our interpretation of the world. Common epistemologies in GIScience include (but are not limited by) positivism and realism. However, many researchers are in effect pragmatists in that they choose the filter that best supports their work and a priori hypotheses. Different epistemologies – or ways of knowing and studying geography – result in different ontologies or classification systems. By understanding the role of epistemology, we can better understand different ways of representing the same phenomena.

FC-02 - Epistemology

Epistemology is the lens through which we view reality. Different epistemologies interpret the earth and patterns on its surface differently. In effect, epistemology is a belief system about the nature of reality that, in turn, structures our interpretation of the world. Common epistemologies in GIScience include (but are not limited by) positivism and realism. However, many researchers are in effect pragmatists in that they choose the filter that best supports their work and a priori hypotheses. Different epistemologies – or ways of knowing and studying geography – result in different ontologies or classification systems. By understanding the role of epistemology, we can better understand different ways of representing the same phenomena.