CV-03 - Vector Formats and Sources

In the last ten years, the rise of efficient computing devices with significant processing power and storage has caused a surge in digital data collection and publication. As more software programs and hardware devices are released, we are not only seeing an increase in available data, but also an increase in available data formats. Cartographers today have access to a wide range of interesting datasets, and online portals for downloading geospatial data now frequently offer that data in several different formats. This chapter provides information useful to modern cartographers working with vector data, including an overview of common vector data formats (e.g. shapefile, GeoJSON, file geodatabase); their relative benefits, idiosyncrasies, and limitations; and a list of popular sources for geospatial vector data (e.g. United States Census Bureau, university data warehouses).

FC-22 - Geometric Primitives and Algorithms

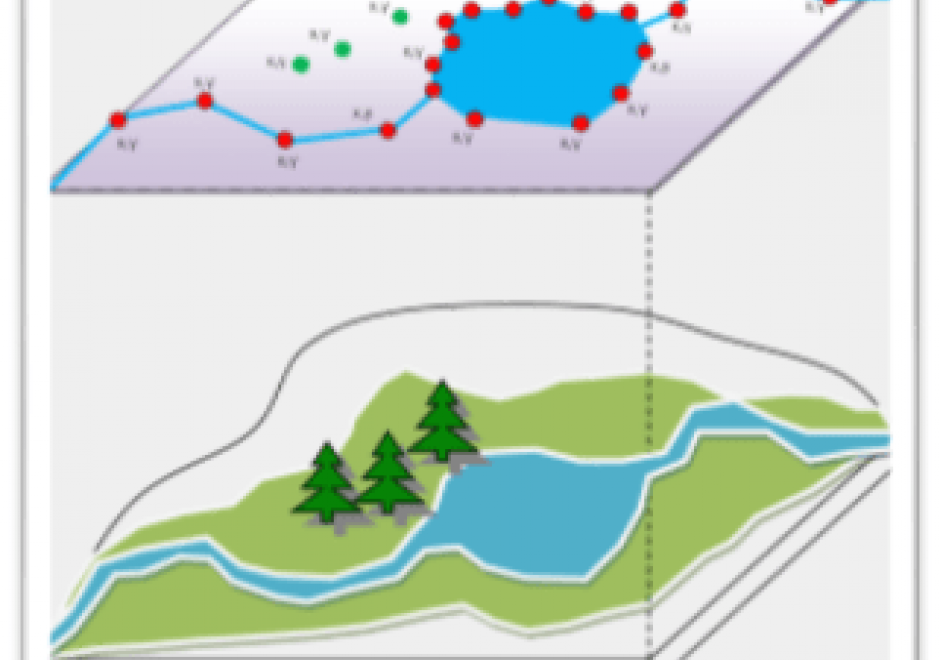

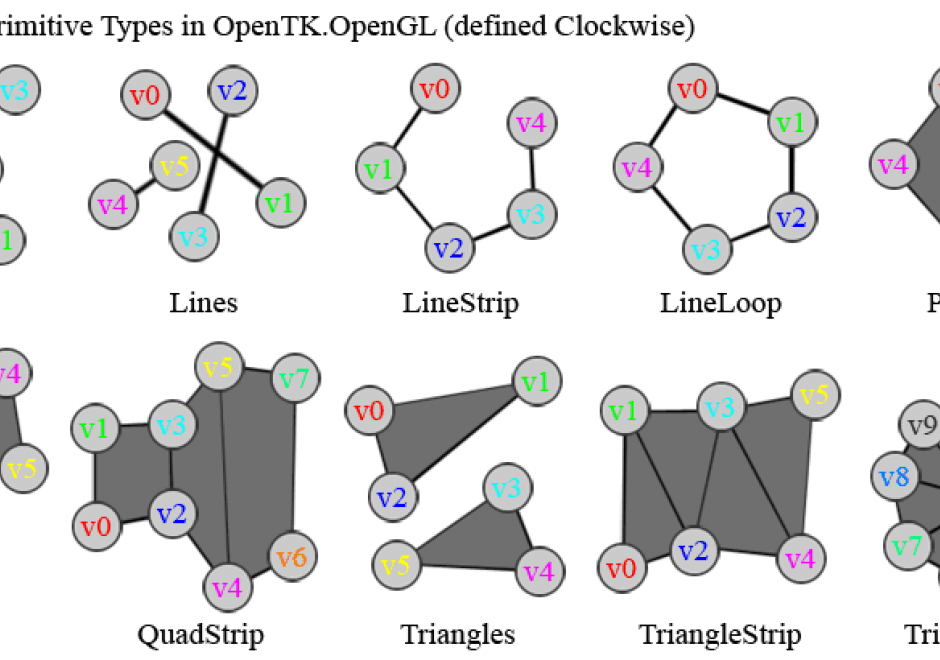

Geometric primitives are the representations used and computations performed in a GIS that concern the spatial aspects of the data, data objects described by coordinates. In vector geometry, we distinguish in zero-, one-, two-, and three-dimensional objects, better known as points, linear features, areal or planar features, and volumetric features. A GIS stores and performs computations on all of these. Often, planar features form a collective known as a (spatial) subdivision. Computations on geometric objects show up in data simplification, neighborhood analysis, spatial clustering, spatial interpolation, automated text placement, segmentation of trajectories, map matching, and many other tasks. They should be contrasted with computations on attributes or networks.

There are various kinds of vector data models for subdivisions. The classical ones are known as spaghetti and pizza models, but nowadays it is recognized that topological data models are the representation of choice. We overview these models briefly.

Computations range from simple to highly complex: deciding whether a point lies in a rectangle needs four comparisons, whereas performing map overlay on two subdivisions requires advanced knowledge of algorithm design. We introduce map overlay, Voronoi diagrams, and Delaunay triangulations and mention algorithmic approaches to compute them.