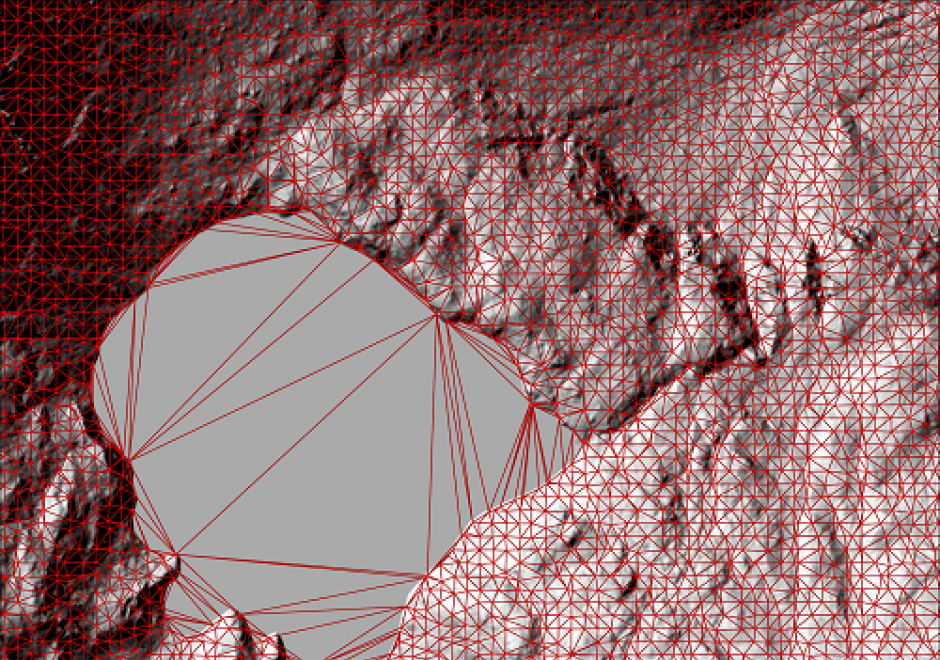

DM-10 - Triangular Irregular Network (TIN) Models

A Triangular Irregular Network (TIN) is a way of storing continuous surfaces. It is vector based, and works in such a way that it connects known data points with straight lines to create triangles, often called facets. These facets are planes that have the same slope and aspect over the facet. Collectively, these hypothetical lines form a network covering the whole surface. TINs are efficient when storing heterogeneous surfaces, since homogenous areas are stored using few data points, while areas with more variability are stored in detail using a larger number of data points. In other words, a TIN can be more detailed where the surface is complex (high variation) by using smaller facets, and less detailed where the surface is more homogeneous by using larger facets. TINs also have a high modelling potential, e.g. in topography and hydrology. However, the unique way of storing data an a TIN often makes it difficult to combine with other spatial data formats. Instead, the TIN data would usually be converted to other suitable formats.

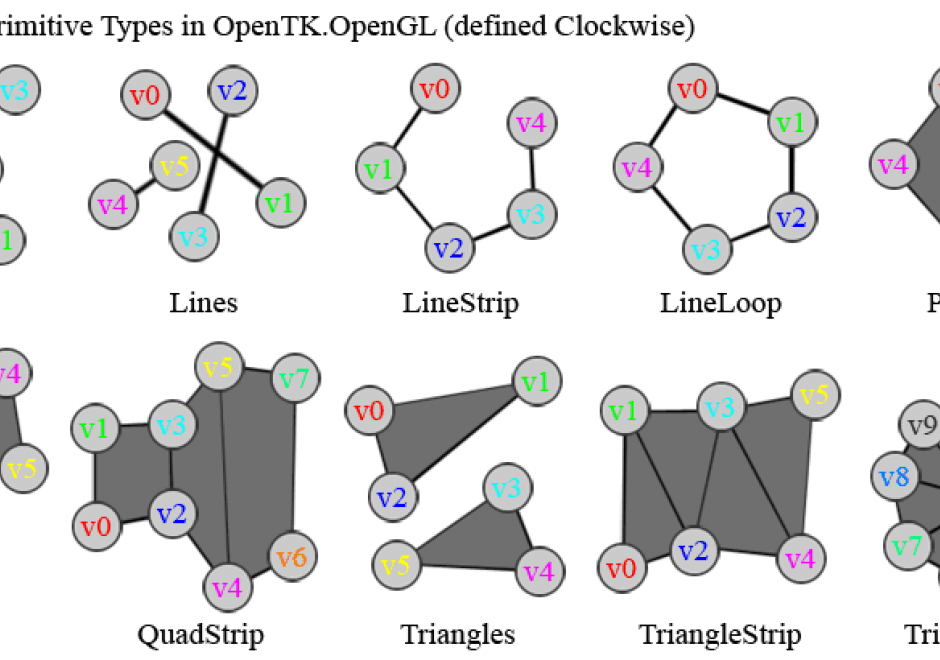

FC-22 - Geometric Primitives and Algorithms

Geometric primitives are the representations used and computations performed in a GIS that concern the spatial aspects of the data, data objects described by coordinates. In vector geometry, we distinguish in zero-, one-, two-, and three-dimensional objects, better known as points, linear features, areal or planar features, and volumetric features. A GIS stores and performs computations on all of these. Often, planar features form a collective known as a (spatial) subdivision. Computations on geometric objects show up in data simplification, neighborhood analysis, spatial clustering, spatial interpolation, automated text placement, segmentation of trajectories, map matching, and many other tasks. They should be contrasted with computations on attributes or networks.

There are various kinds of vector data models for subdivisions. The classical ones are known as spaghetti and pizza models, but nowadays it is recognized that topological data models are the representation of choice. We overview these models briefly.

Computations range from simple to highly complex: deciding whether a point lies in a rectangle needs four comparisons, whereas performing map overlay on two subdivisions requires advanced knowledge of algorithm design. We introduce map overlay, Voronoi diagrams, and Delaunay triangulations and mention algorithmic approaches to compute them.