GS-24 - Citizen Science with GIS&T

Figure 1. Participant in a BioBlitz records bird observation (Source: Jo Somerfield)

Citizen Science is defined as the participation of non-professional volunteers in scientific projects (Dickson et al, 2010) and has experienced rapid growth over the past decade. The projects that are emerging in this area range from contributory projects, co-created projects, collegiate projects, which are initiated and run by a group of people with shared interest, without any involvement of professional scientists.

In many citizen science projects, GIS&T is enabling the collection, analysis, and visualisation of spatial data to affect decision-making. Some examples may include:

- Recording the location of invasive species or participating in a BioBlitz to record local biodiversity (Figure 1).

- Measuring air quality or noise over a large area and over time to monitor local conditions and address them

- Using tools to educate on and increase access to local resources, improving community resilience

Such projects have the opportunity to empower or disempower members of the public, depending upon access to and understanding of technology. Citizen Science projects using GIS&T may help communities influence decision makers and support the gathering of large-scale scientific evidence on a range of issues. This may also renew people’s interests in the sciences and foster continued and lifelong learning.

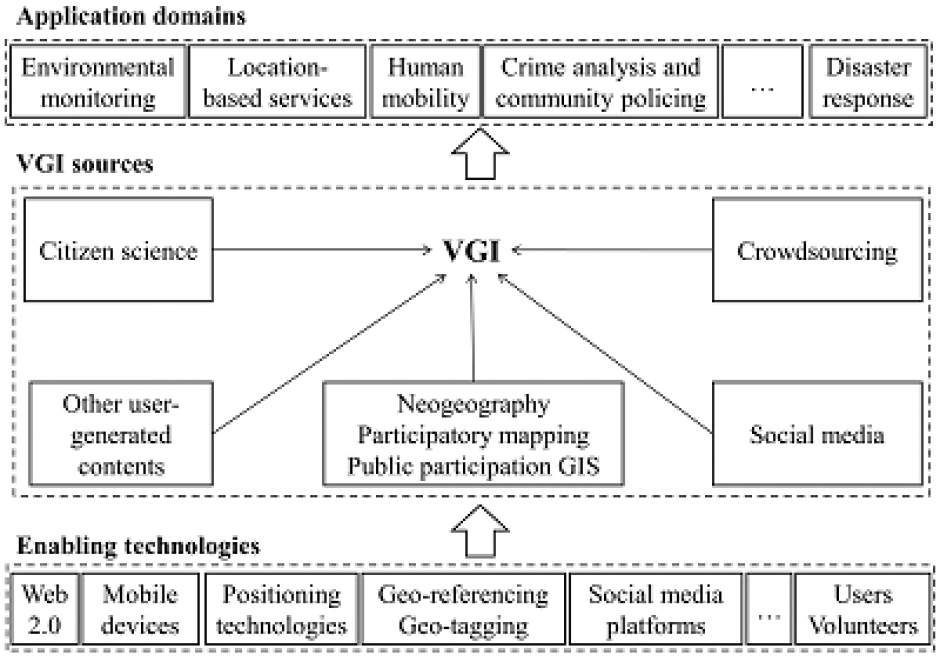

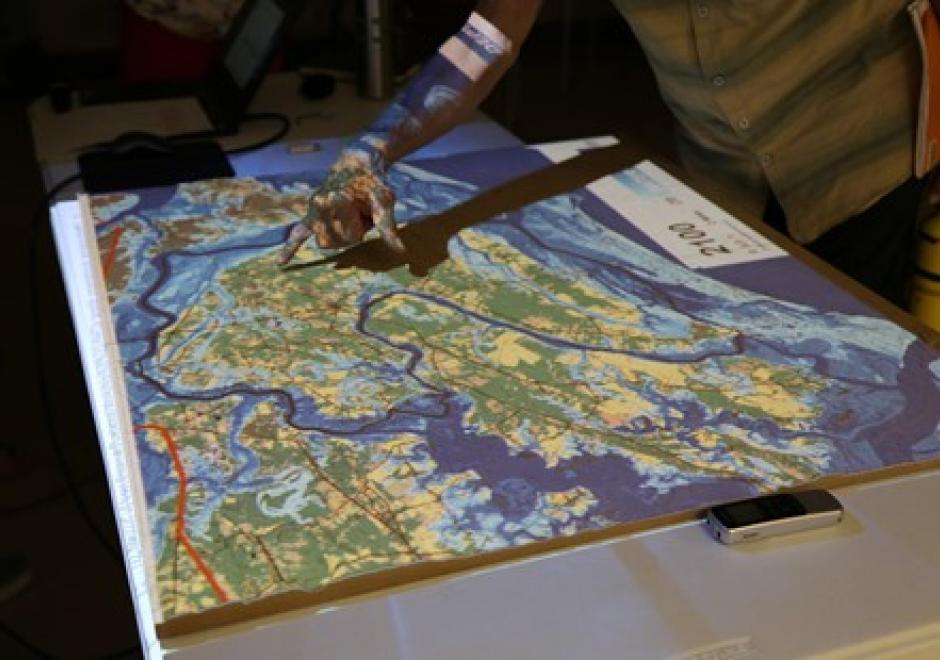

GS-29 - GIS Participatory Modeling

Participatory research is increasingly used to better understand complex social-environmental problems and design solutions through diverse and inclusive stakeholder engagement. A growing number of approaches are helping to foster co-production of knowledge among diverse stakeholders. However, most methods don’t allow stakeholders to directly interact with the models that often drive environmental decision-making. Geospatial participatory modeling (GPM) is an approach that engages stakeholders in co-development and interpretation of models through dynamic geovisualization and simulations. GPM can be used to represent dynamic landscape processes and spatially explicit management scenarios, such as land use change or climate adaptation, enhancing opportunities for co-learning. GPM can provide multiple benefits over non-spatial approaches for participatory research processes, by (a) personalizing connections to problems and their solutions, (b) resolving abstract notions of connectivity, and (c) clarifying the scales of drivers, data, and decision-making authority. An adaptive, iterative process of model development, sharing, and revision can drive innovation of methods, improve model realism or applicability, and build capacity for stakeholders to leverage new knowledge gained from the process. This co-production of knowledge enables participants to more fully understand problems, evaluate the acceptability of trade-offs, and build buy-in for management actions in the places where they live and work.