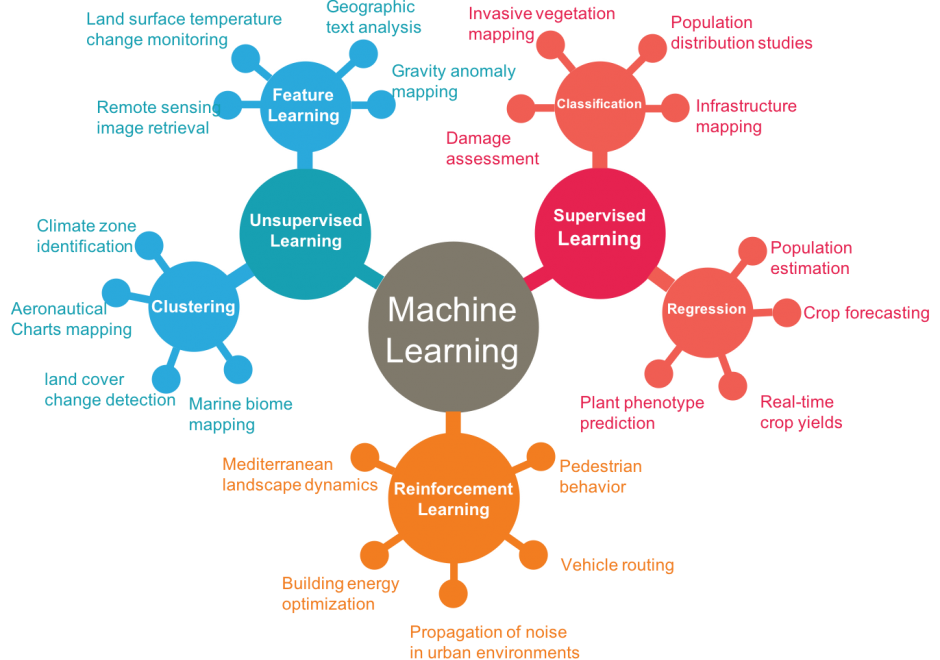

CV-03 - Vector Formats and Sources

In the last ten years, the rise of efficient computing devices with significant processing power and storage has caused a surge in digital data collection and publication. As more software programs and hardware devices are released, we are not only seeing an increase in available data, but also an increase in available data formats. Cartographers today have access to a wide range of interesting datasets, and online portals for downloading geospatial data now frequently offer that data in several different formats. This chapter provides information useful to modern cartographers working with vector data, including an overview of common vector data formats (e.g. shapefile, GeoJSON, file geodatabase); their relative benefits, idiosyncrasies, and limitations; and a list of popular sources for geospatial vector data (e.g. United States Census Bureau, university data warehouses).

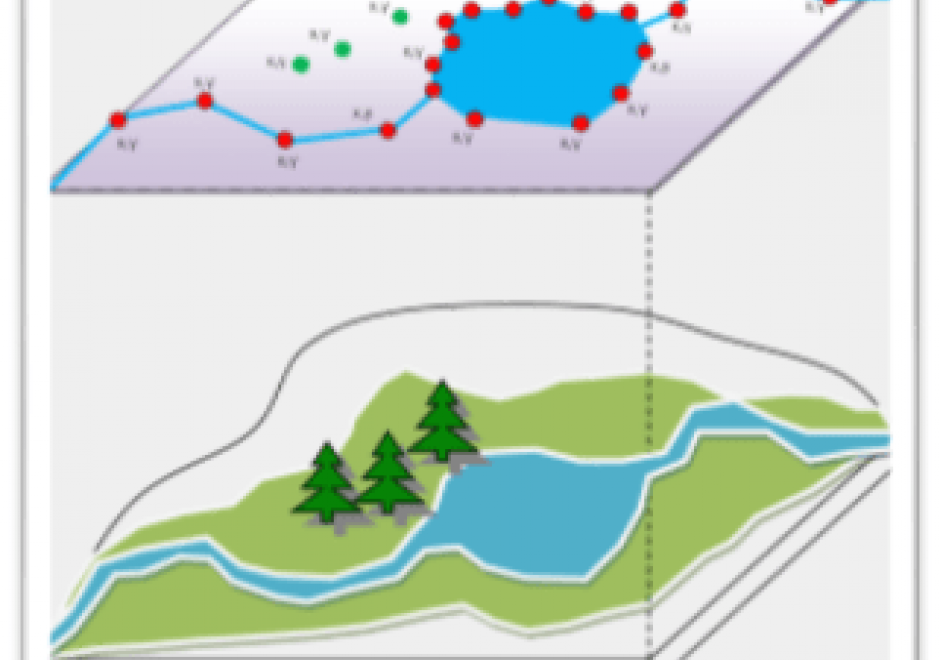

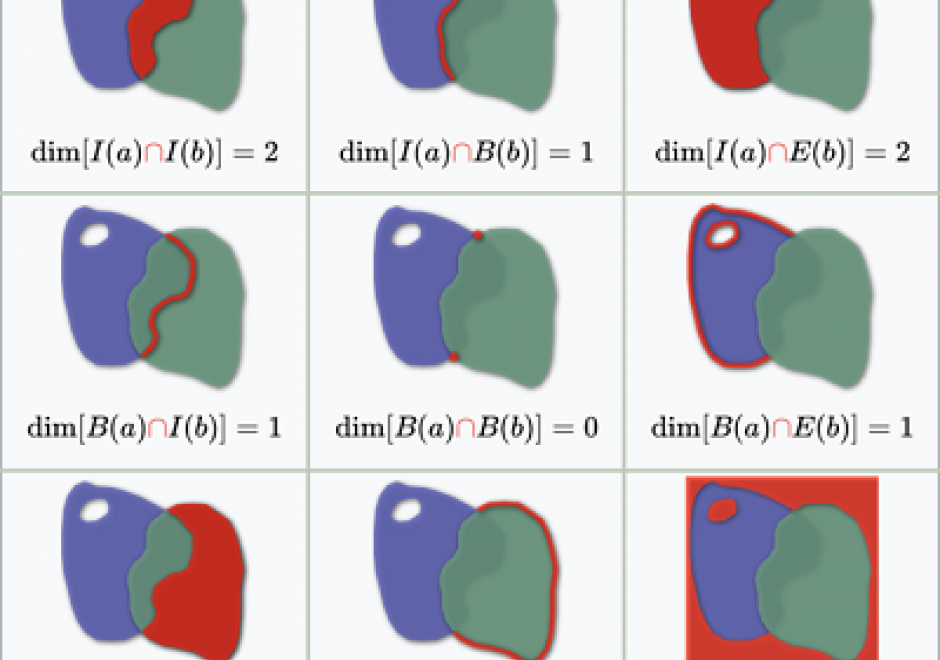

AM-107 - Spatial Data Uncertainty

Although spatial data users may not be aware of the inherent uncertainty in all the datasets they use, it is critical to evaluate data quality in order to understand the validity and limitations of any conclusions based on spatial data. Spatial data uncertainty is inevitable as all representations of the real world are imperfect. This topic presents the importance of understanding spatial data uncertainty and discusses major methods and models to communicate, represent, and quantify positional and attribute uncertainty in spatial data, including both analytical and simulation approaches. Geo-semantic uncertainty that involves vague geographic concepts and classes is also addressed from the perspectives of fuzzy-set approaches and cognitive experiments. Potential methods that can be implemented to assess the quality of large volumes of crowd-sourced geographic data are also discussed. Finally, this topic ends with future directions to further research on spatial data quality and uncertainty.