CV-19 - Big Data Visualization

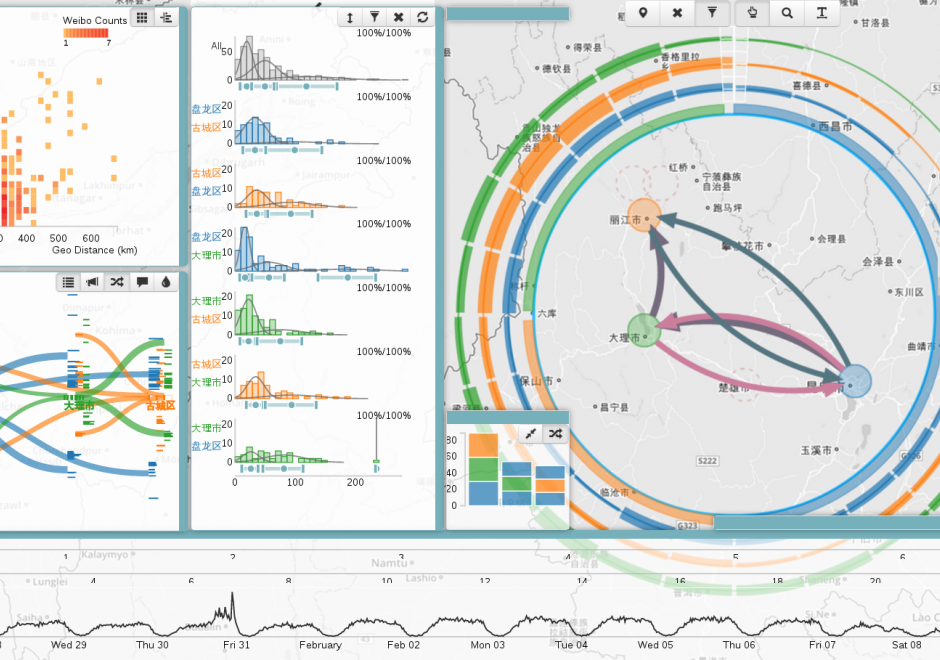

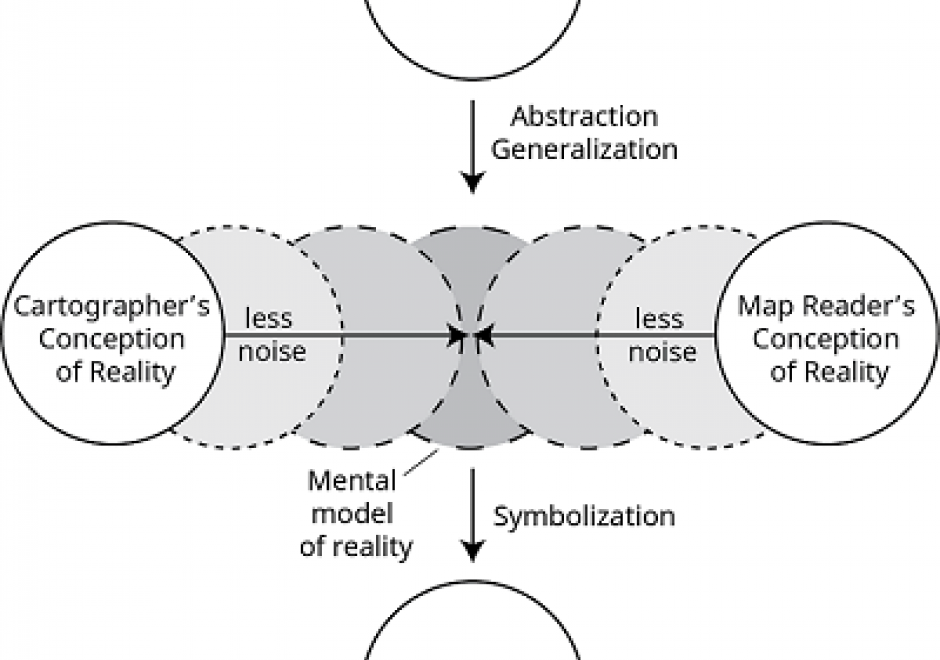

As new information and communication technologies have altered so many aspects of our daily lives over the past decades, they have simultaneously stimulated a shift in the types of data that we collect, produce, and analyze. Together, this changing data landscape is often referred to as "big data." Big data is distinguished from "small data" not only by its high volume but also by the velocity, variety, exhaustivity, resolution, relationality, and flexibility of the datasets. This entry discusses the visualization of big spatial datasets. As many such datasets contain geographic attributes or are situated and produced within geographic space, cartography takes on a pivotal role in big data visualization. Visualization of big data is frequently and effectively used to communicate and present information, but it is in making sense of big data – generating new insights and knowledge – that visualization is becoming an indispensable tool, making cartography vital to understanding geographic big data. Although visualization of big data presents several challenges, human experts can use visualization in general, and cartography in particular, aided by interfaces and software designed for this purpose, to effectively explore and analyze big data.

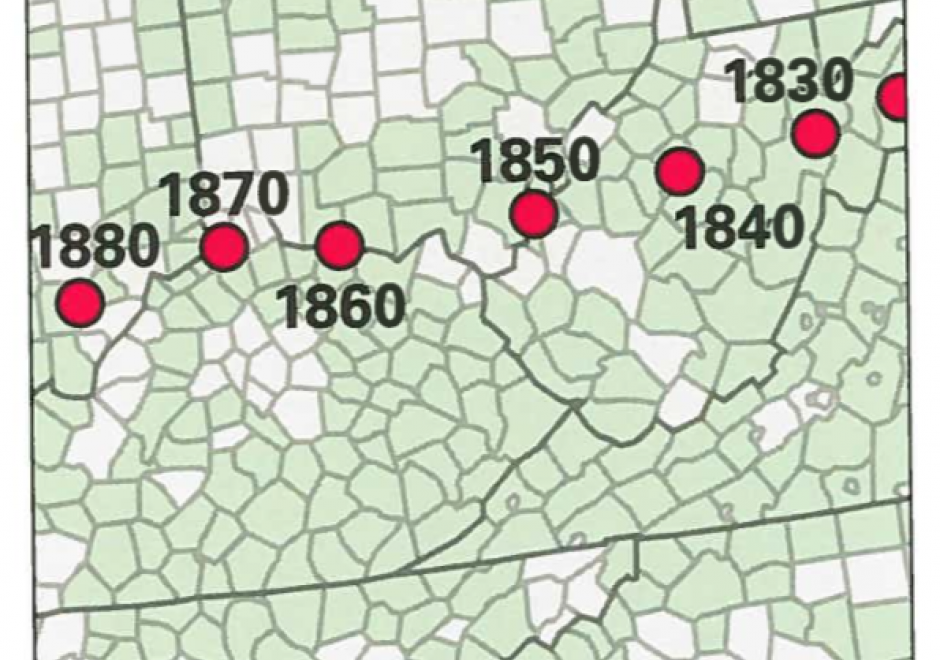

AM-106 - Error-based Uncertainty

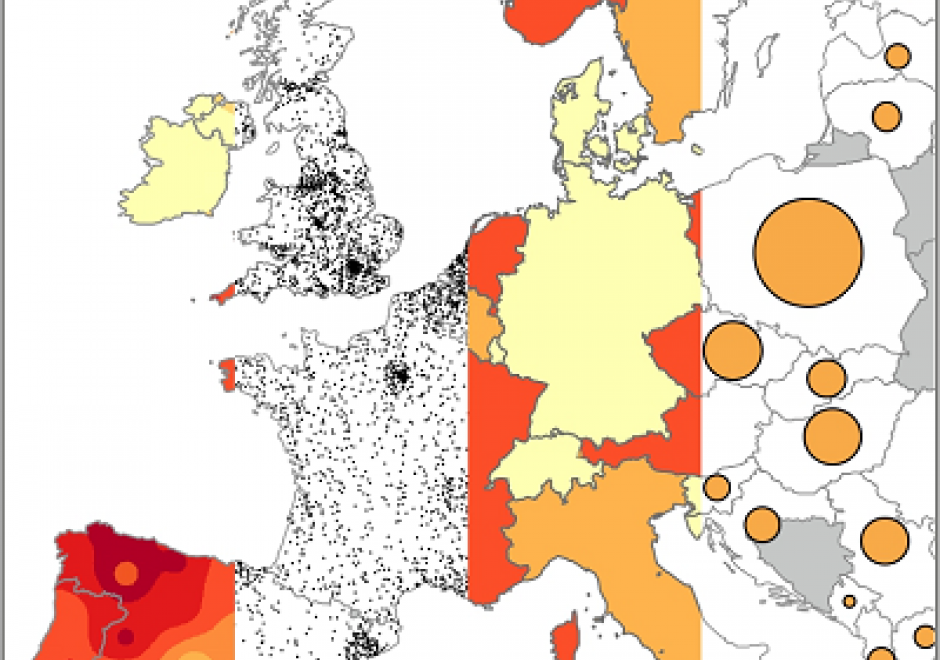

The largest contributing factor to spatial data uncertainty is error. Error is defined as the departure of a measure from its true value. Uncertainty results from: (1) a lack of knowledge of the extent and of the expression of errors and (2) their propagation through analyses. Understanding error and its sources is key to addressing error-based uncertainty in geospatial practice. This entry presents a sample of issues related to error and error based uncertainty in spatial data. These consist of (1) types of error in spatial data, (2) the special case of scale and its relationship to error and (3) approaches to quantifying error in spatial data.