GS-15 - Feminist Critiques of GIS

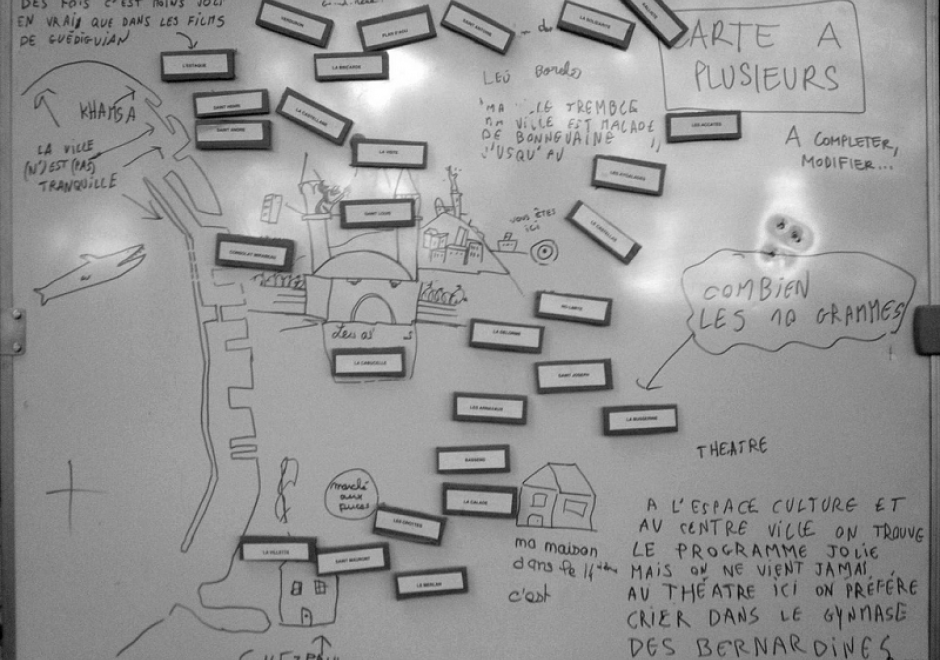

Feminist interactions with GIS started in the 1990s in the form of strong critiques against GIS inspired by feminist and postpositivist theories. Those critiques mainly highlighted a supposed epistemological dissonance between GIS and feminist scholarship. GIS was accused of being shaped by positivist and masculinist epistemologies, especially due to its emphasis on vision as the principal way of knowing. In addition, feminist critiques claimed that GIS was largely incompatible with positionality and reflexivity, two core concepts of feminist theory. Feminist critiques of GIS also discussed power issues embedded in GIS practices, including the predominance of men in the early days of the GIS industry and the development of GIS practices for the military and surveillance purposes.

At the beginning of the 21st century, feminist geographers reexamined those critiques and argued against an inherent epistemological incompatibility between GIS methods and feminist scholarship. They advocated for a reappropriation of GIS by feminist scholars in the form of critical feminist GIS practices. The critical GIS perspective promotes an unorthodox, reconstructed, and emancipatory set of GIS practices by critiquing dominant approaches of knowledge production, implementing GIS in critically informed progressive social research, and developing postpositivist techniques of GIS. Inspired by those debates, feminist scholars did reclaim GIS and effectively developed feminist GIS practices.

CP-04 - Artificial Intelligence Tools and Platforms for GIS

Artificial intelligence is the study of intelligence agents as demonstrated by machines. It is an interdisciplinary field involving computer science as well as, various kinds of engineering and science, for example, robotics, bio-medical engineering, that accentuates automation of human acts and intelligence through machines. AI represents state-of-the-art use of machines to bring about algorithmic computation and understanding of tasks that include learning, problem solving, mapping, perception, and reasoning. Given the data and a description of its properties and relations between objects of interest, AI methods can perform the aforementioned tasks. Widely applied AI capabilities, e.g. learning, are now achievable at large scale through machine learning (ML), large volumes of data and specialized computational machines. ML encompasses learning without any kind of supervision (unsupervised learning) and learning with full supervision (supervised learning). Widely applied supervised learning techniques include deep learning and other machine learning methods that require less data than deep learning e.g. support vector machines, random forests. Unsupervised learning examples include dictionary learning, independent component analysis, and autoencoders. For application tasks with less labeled data, both supervised and unsupervised techniques can be adapted in a semi-supervised manner to produce accurate models and to increase the size of the labeled training data.