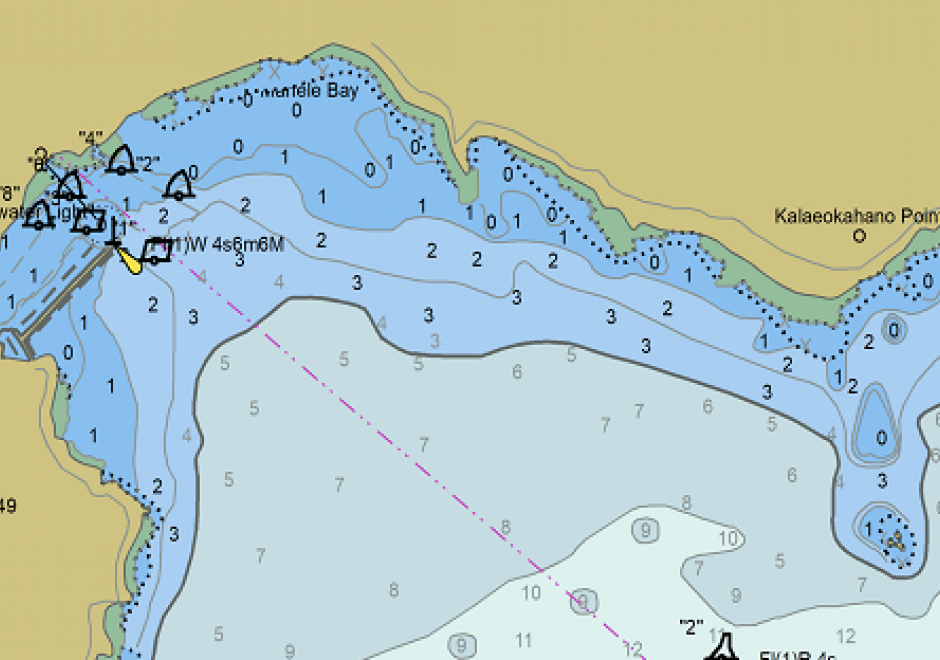

DM-90 - Hydrographic Geospatial Data Standards

Coastal nations, through their dedicated Hydrographic Offices (HOs), have the obligation to provide nautical charts for the waters of national jurisdiction in support of safe maritime navigation. Accurate and reliable charts are essential to seafarers whether for commerce, defense, fishing, or recreation. Since navigation can be an international activity, mariners often use charts published from different national HOs. Standardization of data collection and processing, chart feature generalization methods, text, symbology, and output validation becomes essential in providing mariners with consistent and uniform products regardless of the region or the producing nation. Besides navigation, nautical charts contain information about the seabed and the coastal environment useful in other domains such as dredging, oceanography, geology, coastal modelling, defense, and coastal zone management. The standardization of hydrographic and nautical charting activities is achieved through various publications issued by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). This chapter discusses the purpose and importance of nautical charts, the establishment and role of the IHO in coordinating HOs globally, the existing hydrographic geospatial data standards, as well as those under development based on the new S-100 Universal Hydrographic Data Model.

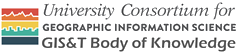

DM-85 - Point, Line, and Area Generalization

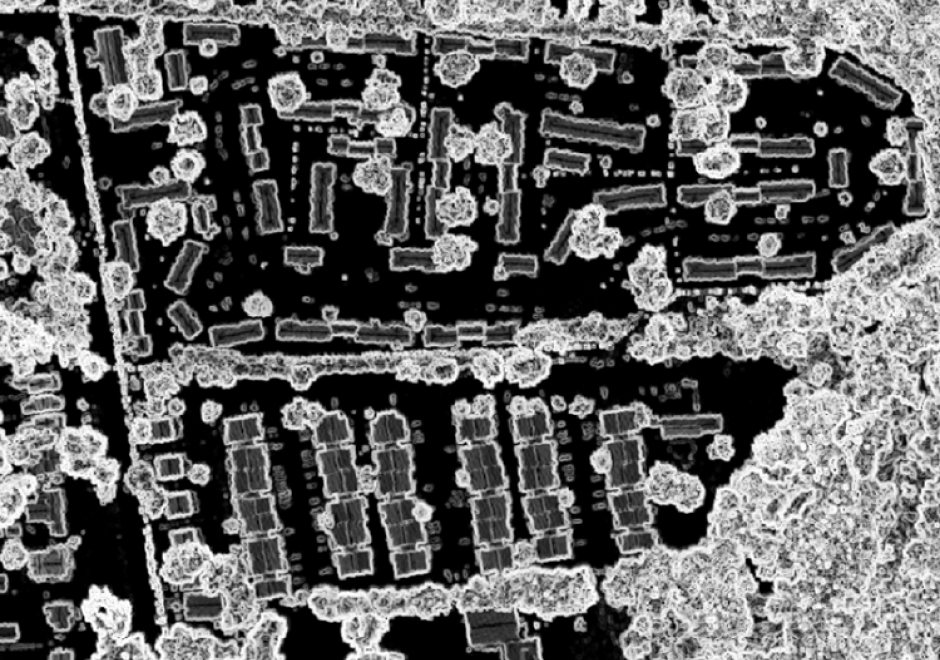

Generalization is an important and unavoidable part of making maps because geographic features cannot be represented on a map without undergoing transformation. Maps abstract and portray features using vector (i.e. points, lines and polygons) and raster (i.e pixels) spatial primitives which are usually labeled. These spatial primitives are subjected to further generalization when map scale is changed. Generalization is a contradictory process. On one hand, it alters the look and feel of a map to improve overall user experience especially regarding map reading and interpretive analysis. On the other hand, generalization has documented quality implications and can sacrifice feature detail, dimensions, positions or topological relationships. A variety of techniques are used in generalization and these include selection, simplification, displacement, exaggeration and classification. The techniques are automated through computer algorithms such as Douglas-Peucker and Visvalingam-Whyatt in order to enhance their operational efficiency and create consistent generalization results. As maps are now created easily and quickly, and used widely by both experts and non-experts owing to major advances in IT, it is increasingly important for virtually everyone to appreciate the circumstances, techniques and outcomes of generalizing maps. This is critical to promoting better map design and production as well as socially appropriate uses.