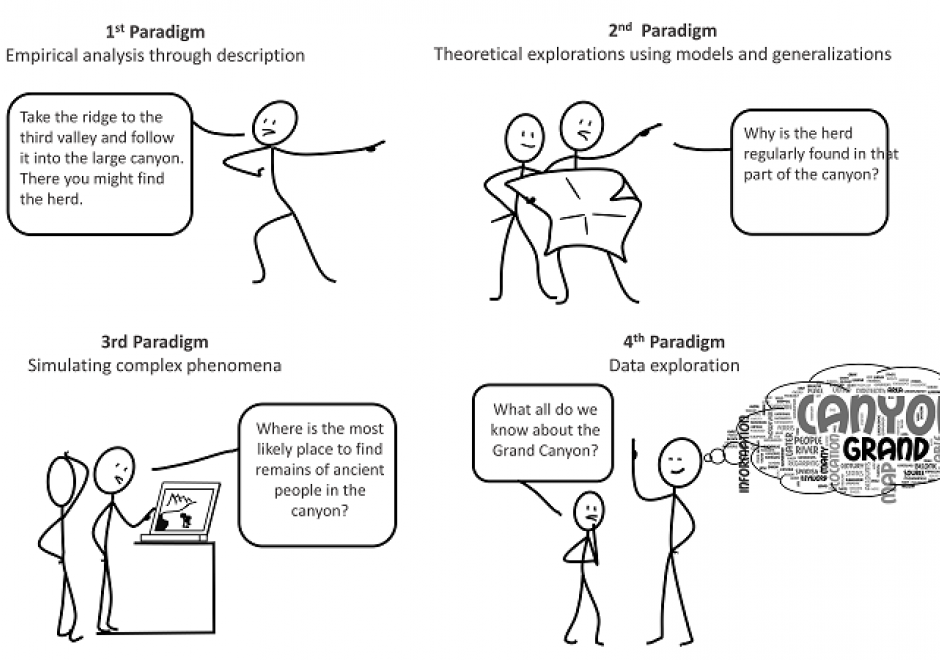

AM-21 - The Evolution of Geospatial Reasoning, Analytics, and Modeling

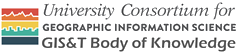

The field of geospatial analytics and modeling has a long history coinciding with the physical and cultural evolution of humans. This history is analyzed relative to the four scientific paradigms: (1) empirical analysis through description, (2) theoretical explorations using models and generalizations, (3) simulating complex phenomena and (4) data exploration. Correlations among developments in general science and those of the geospatial sciences are explored. Trends identify areas ripe for growth and improvement in the fourth and current paradigm that has been spawned by the big data explosion, such as exposing the ‘black box’ of GeoAI training and generating big geospatial training datasets. Future research should focus on integrating both theory- and data-driven knowledge discovery.

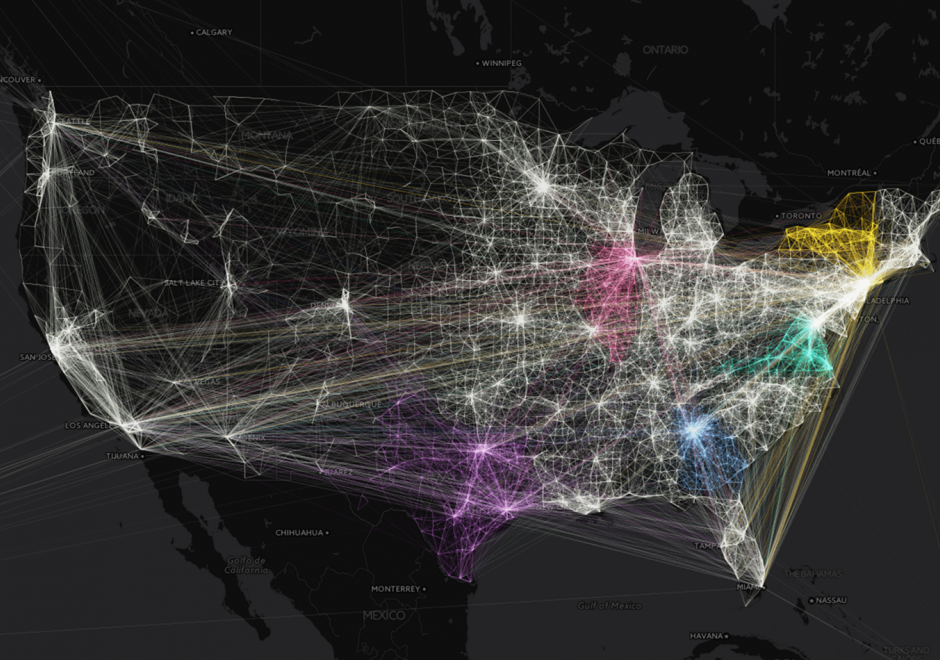

AM-94 - Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning approaches are increasingly used across numerous applications in order to learn from data and generate new knowledge discoveries, advance scientific studies and support automated decision making. In this knowledge entry, the fundamentals of Machine Learning (ML) are introduced, focusing on how feature spaces, models and algorithms are being developed and applied in geospatial studies. An example of a ML workflow for supervised/unsupervised learning is also introduced. The main challenges in ML approaches and our vision for future work are discussed at the end.