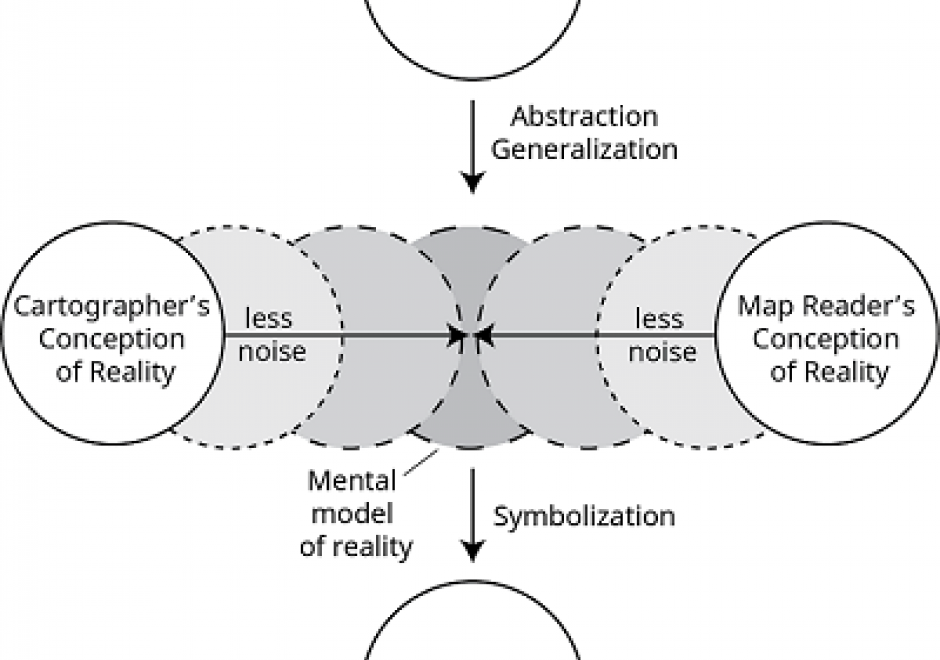

CV-01 - Cartography and Science

"Science" is used both to describe a general, systematic approach to understanding the world and to refer to that approach as it is applied to a specific phenomenon of interest, for example, "geographic information science." The scientific method is used to develop theories that explain phenomena and processes. It consists of an iterative cycle of several steps: proposing a hypothesis, devising a way to make empirical observations that test that hypothesis, and finally, refining the hypothesis based on the empirical observations. "Scientific cartography" became a dominant mode of cartographic research and inquiry after World War II, when there was increased focus on the efficacy of particular design decisions and how particular maps were understood by end users. This entry begins with a brief history of the development of scientific cartographic approaches, including how they are deployed in map design research today. Next it discusses how maps have been used by scientists to support scientific thinking. Finally, it concludes with a discussion of how maps are used to communicate the results of scientific thinking.

CV-17 - Spatiotemporal Representation

Space and time are integral components of geographic information. There are many ways in which to conceptualize space and time in the geographic realm that stem from time geography research in the 1960s. Cartographers and geovisualization experts alike have grappled with how to represent spatiotemporal data visually. Four broad types of mapping techniques allow for a variety of representations of spatiotemporal data: (1) single static maps, (2) multiple static maps, (3) single dynamic maps, and (4) multiple dynamic maps. The advantages and limitations of these static and dynamic methods are discussed in this entry. For cartographers, identifying the audience and purpose, medium, available data, and available time to design the map are vital aspects to deciding between the different spatiotemporal mapping techniques. However, each of these different mapping techniques offers its own advantages and disadvantages to the cartographer and the map reader. This entry focuses on the mapping of time and spatiotemporal data, the types of time, current methods of mapping, and the advantages and limitations of representing spatiotemporal data.