CV-08 - Symbolization and the Visual Variables

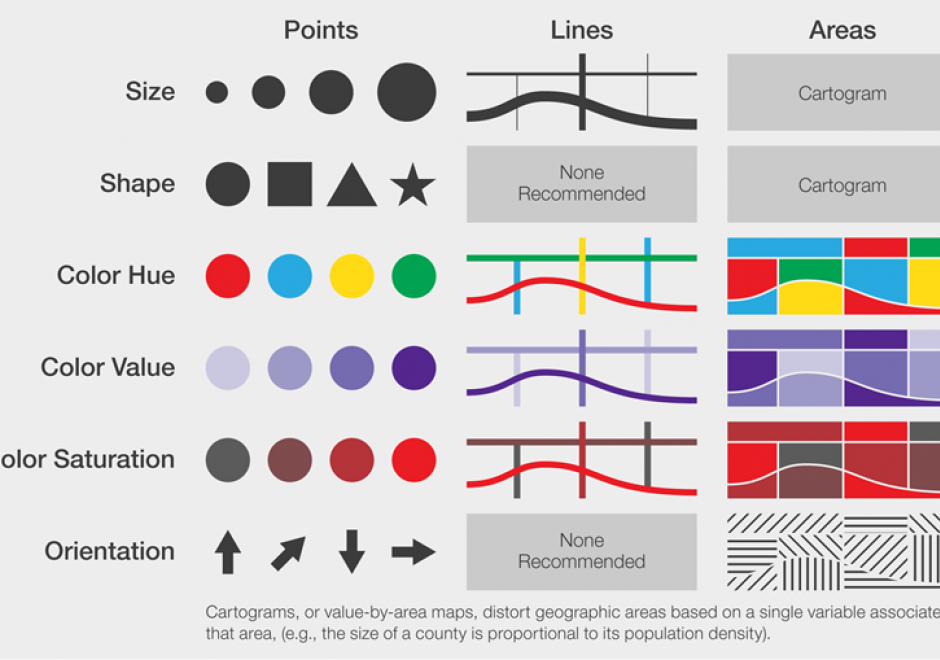

Maps communicate information about the world by using symbols to represent specific ideas or concepts. The relationship between a map symbol and the information that symbol represents must be clear and easily interpreted. The symbol design process requires first an understanding of the underlying nature of the data to be mapped (e.g., its spatial dimensions and level of measurement), then the selection of symbols that suggest those data attributes. Cartographers developed the visual variable system, a graphic vocabulary, to express these relationships on maps. Map readers respond to the visual variable system in predictable ways, enabling mapmakers to design map symbols for most types of information with a high degree of reliability.

CV-21 - Map Reading

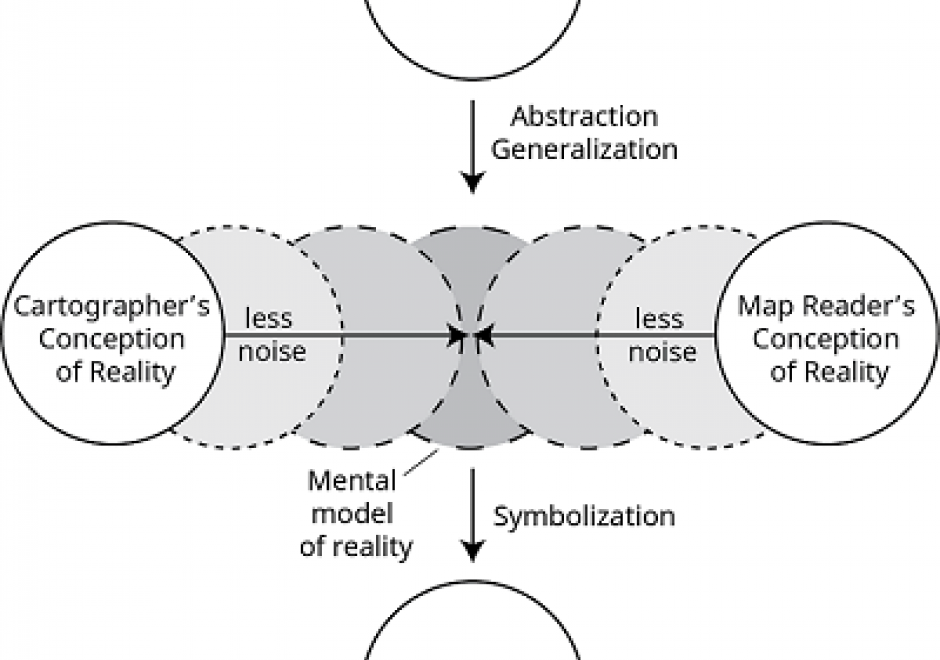

Map reading is the process of looking at the map to determine what is depicted and how the cartographer depicted it. This involves identifying the features or phenomena portrayed, the symbols and labels used, and information about the map that may not be displayed on the map. Reading maps accurately and effectively requires at least a basic understanding of how the mapmaker has made important cartographic decisions relating to map scale, map projections, coordinate systems, and cartographic compilation (selection, classification, generalization, and symbolization). Proficient map readers also appreciate artifacts of the cartographic compilation process that improve readability but may also affect map accuracy and uncertainty. Masters of map reading use maps to gain better understanding of their environment, develop better mental maps, and ultimately make better decisions. Through successful map reading, a person’s cartographic and mental maps will merge to tune the reader’s spatial thinking to the reality of the environment.