DM-20 - Discrete entities

- Discuss the human predilection to conceptualize geographic phenomena in terms of discrete entities

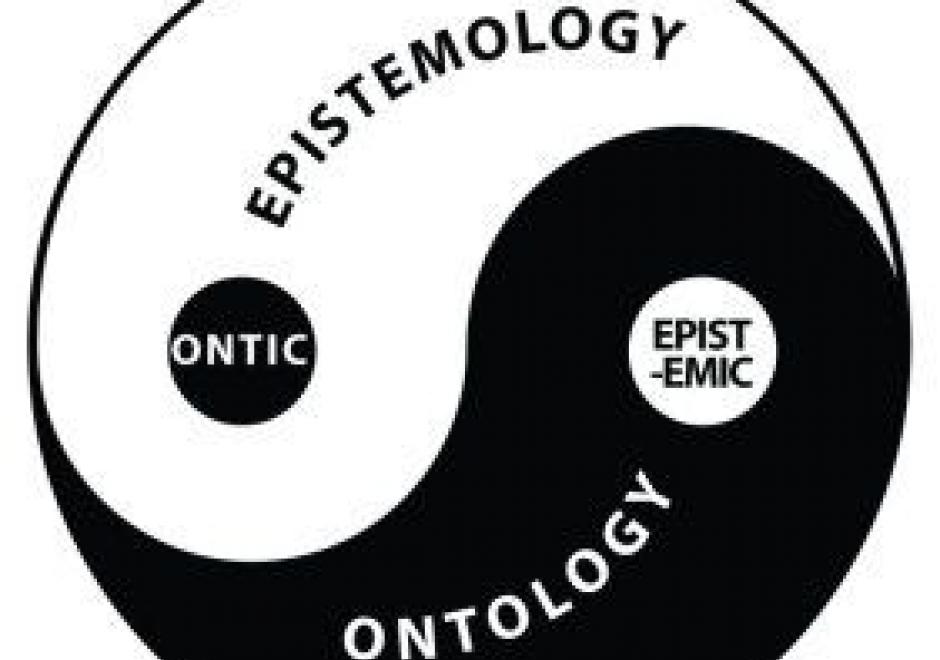

- Compare and contrast differing epistemological and metaphysical viewpoints on the “reality” of geographic entities

- Identify the types of features that need to be modeled in a particular GIS application or procedure

- Identify phenomena that are difficult or impossible to conceptualize in terms of entities

- Describe the difficulties in modeling entities with ill-defined edges

- Describe the difficulties inherent in extending the “tabletop” metaphor of objects to the geographic environment

- Evaluate the effectiveness of GIS data models for representing the identity, existence, and lifespan of entities

- Justify or refute the conception of fields (e.g., temperature, density) as spatially-intensive attributes of (sometimes amorphous and anonymous) entities

- Model “gray area” phenomena, such as categorical coverages (a.k.a. discrete fields), in terms of objects

- Evaluate the influence of scale on the conceptualization of entities

- Describe the perceptual processes (e.g., edge detection) that aid cognitive objectification

- Describe particular entities in terms of space, time, and properties

PD-05 - Design, Development, Testing, and Deployment of GIS Applications

A systems development life cycle (SDLC) denes and guides the activities and milestones in the design, development, testing, and de ployment of software applications & information systems. Various choices of SDLC are available for different types of software applications & information systems and compositions of development teams and stakeholders. While the choice of an SDLC for building geographic information system (GIS) applications is similar to that of other types of software applications, critical decisions in each phase of the GIS development life cycle (GiSDLC) should take into account essential questions concern ing the storage, access, and analysis of (geo)spatial data for the target application. This article aims to introduce various considerations in the GiSDLC, from the perspectives of handling (geo)spatial data. The article rst introduces several (geo)spatial processes and types as well as various modalities of GIS applications. Then the article gives a brief introduction to an SDLC, including explaining the role of (geo)spatial data in the SDLC. Finally, the article uses two existing real-world applications as an example to highlight critical considerations in the GiSDLC.