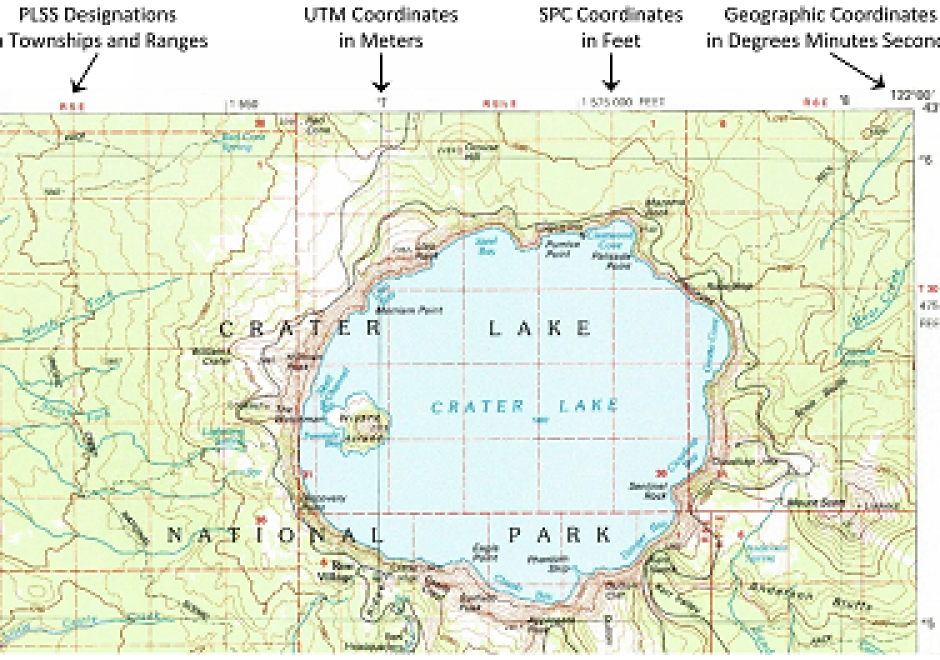

CV-21 - Map Reading

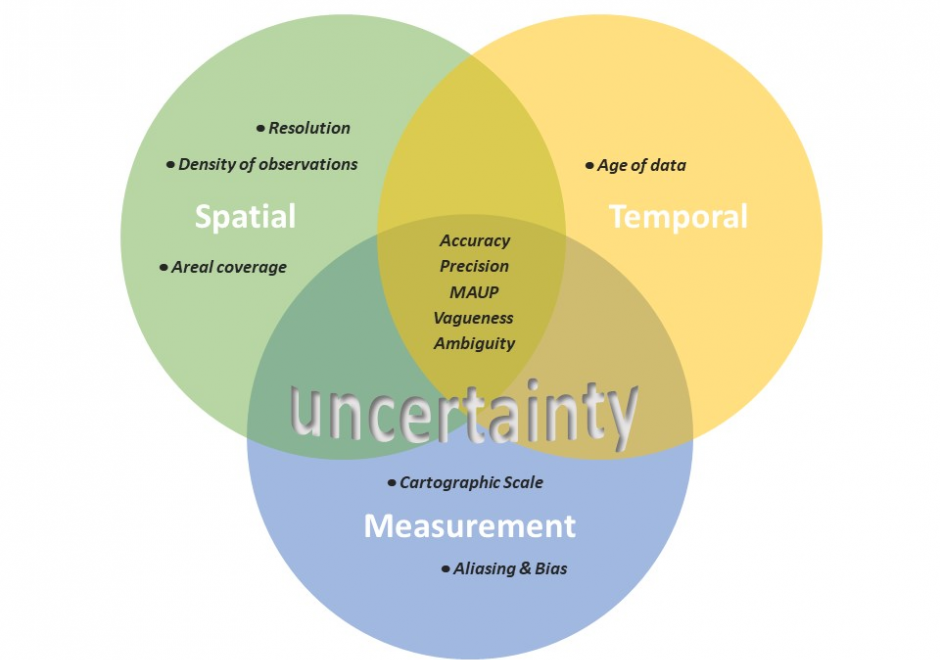

Map reading is the process of looking at the map to determine what is depicted and how the cartographer depicted it. This involves identifying the features or phenomena portrayed, the symbols and labels used, and information about the map that may not be displayed on the map. Reading maps accurately and effectively requires at least a basic understanding of how the mapmaker has made important cartographic decisions relating to map scale, map projections, coordinate systems, and cartographic compilation (selection, classification, generalization, and symbolization). Proficient map readers also appreciate artifacts of the cartographic compilation process that improve readability but may also affect map accuracy and uncertainty. Masters of map reading use maps to gain better understanding of their environment, develop better mental maps, and ultimately make better decisions. Through successful map reading, a person’s cartographic and mental maps will merge to tune the reader’s spatial thinking to the reality of the environment.

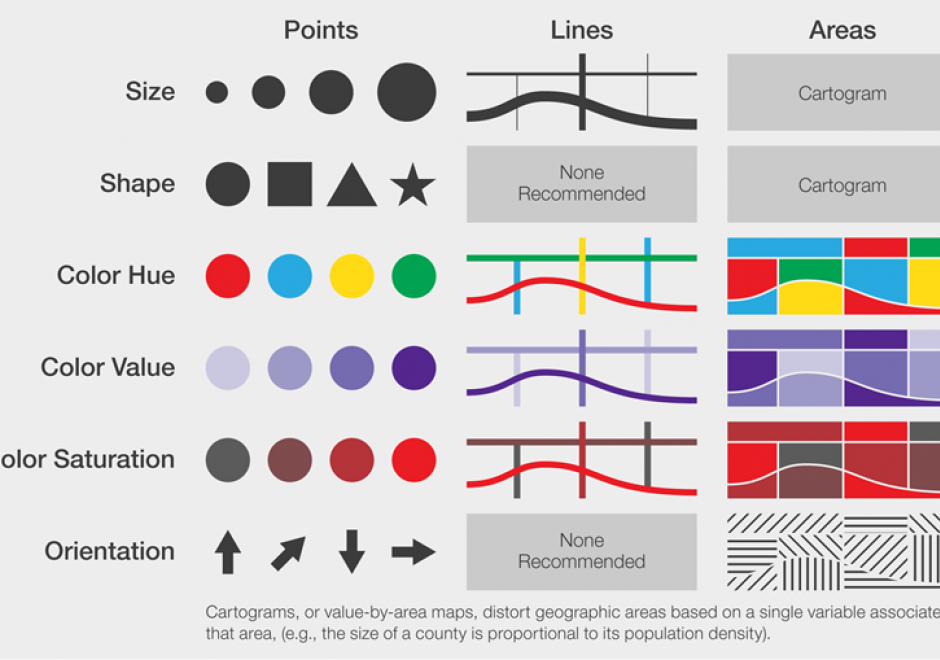

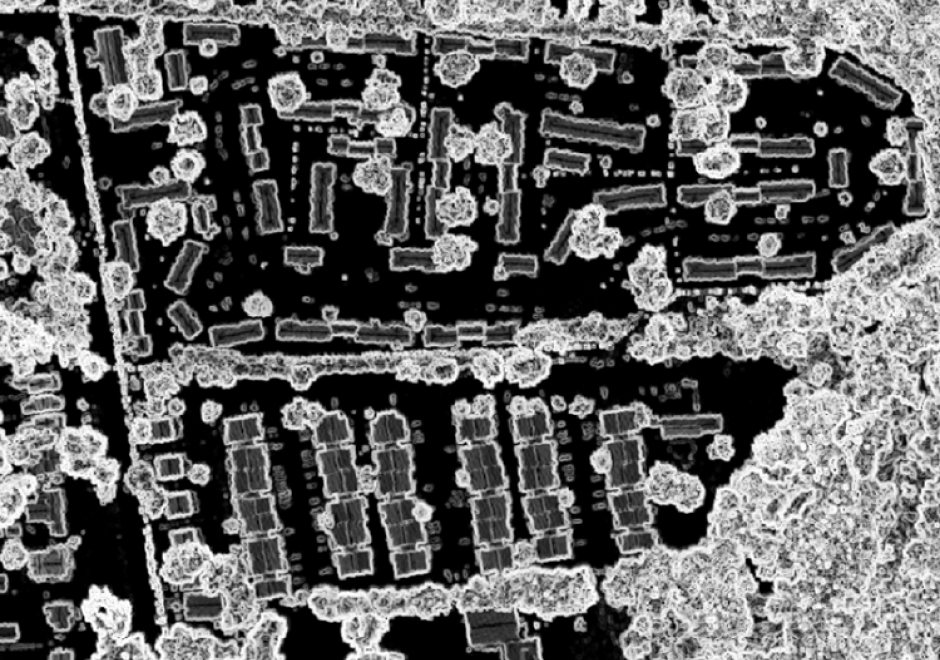

DM-85 - Point, Line, and Area Generalization

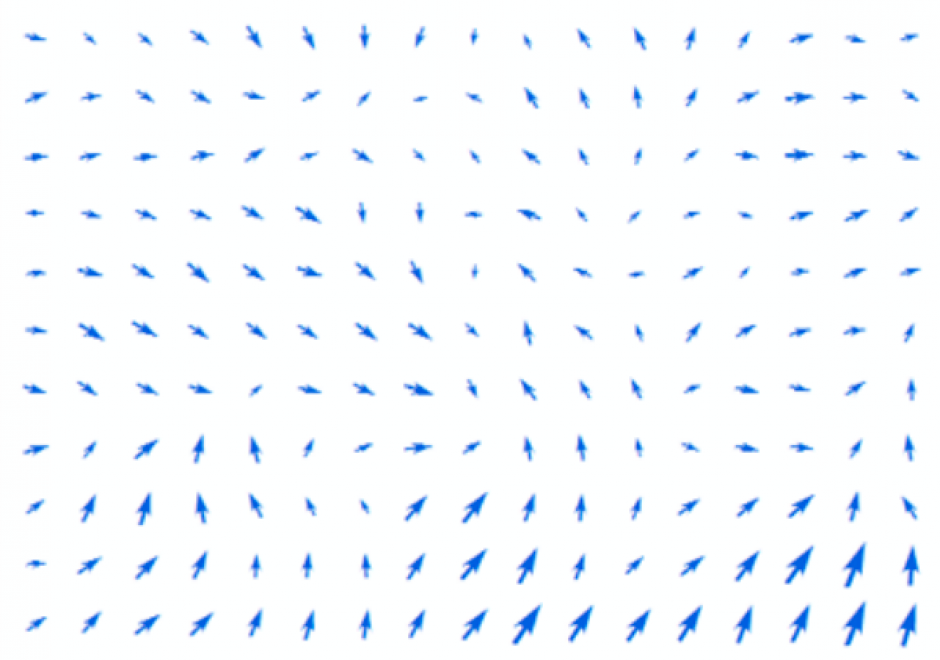

Generalization is an important and unavoidable part of making maps because geographic features cannot be represented on a map without undergoing transformation. Maps abstract and portray features using vector (i.e. points, lines and polygons) and raster (i.e pixels) spatial primitives which are usually labeled. These spatial primitives are subjected to further generalization when map scale is changed. Generalization is a contradictory process. On one hand, it alters the look and feel of a map to improve overall user experience especially regarding map reading and interpretive analysis. On the other hand, generalization has documented quality implications and can sacrifice feature detail, dimensions, positions or topological relationships. A variety of techniques are used in generalization and these include selection, simplification, displacement, exaggeration and classification. The techniques are automated through computer algorithms such as Douglas-Peucker and Visvalingam-Whyatt in order to enhance their operational efficiency and create consistent generalization results. As maps are now created easily and quickly, and used widely by both experts and non-experts owing to major advances in IT, it is increasingly important for virtually everyone to appreciate the circumstances, techniques and outcomes of generalizing maps. This is critical to promoting better map design and production as well as socially appropriate uses.