PD-32 - JavaScript for GIS

JavaScript (which has no connection to the Java computer language) is a popular high-level programming languages used to develop user interfaces in web pages. The principle goal of using JavaScript for programming web and mobile GIS applications is to build front-end applications that make use of spatial data and GIS principles, and in many cases, have embedded, interactive maps. It is considered much easier to program than Java or C languages for adding automation, animation, and interactivity into web pages and applications. JavaScript uses the leading browsers as runtime environments (RTE) and thus benefits from rapid and continuously evolving browser support for all web and mobile applications.

AM-17 - Intervisibility, Line-of-Sight, and Viewsheds

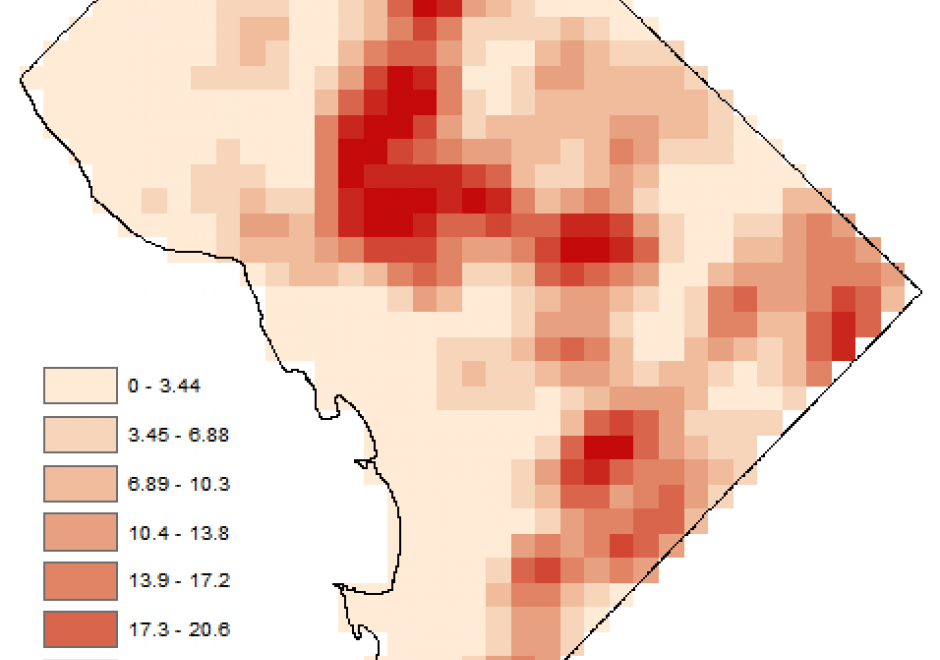

The visibility of a place refers to whether it can be seen by observers from one or multiple other locations. Modeling the visibility of points has various applications in GIS, such as placement of observation points, military observation, line-of-sight communication, optimal path route planning, and urban design. This chapter provides a brief introduction to visibility analysis, including an overview of basic conceptions in visibility analysis, the methods for computing intervisibility using discrete and continuous approaches based on DEM and TINs, the process of intervisibility analysis, viewshed and reverse viewshed analysis. Several practical applications involving visibility analysis are illustrated for geographical problem-solving. Finally, existing software and toolboxes for visibility analysis are introduced.