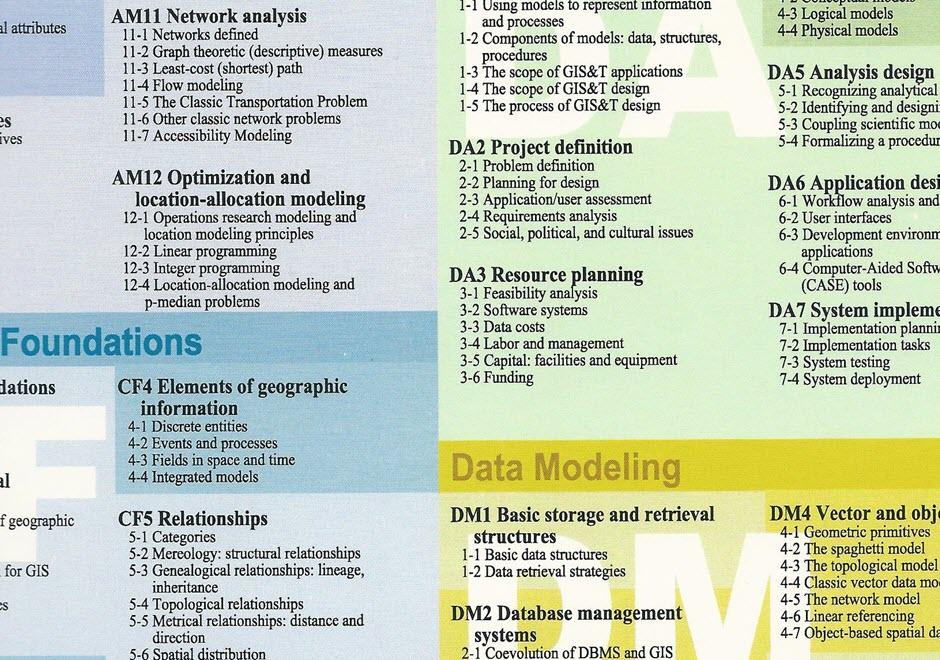

AM-32 - Spatial Autoregressive Models

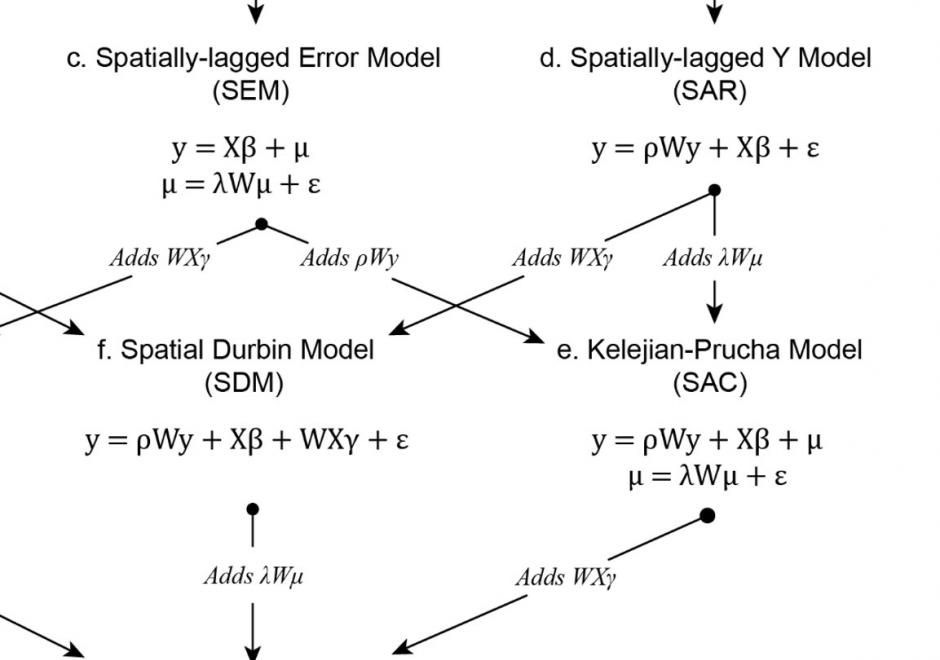

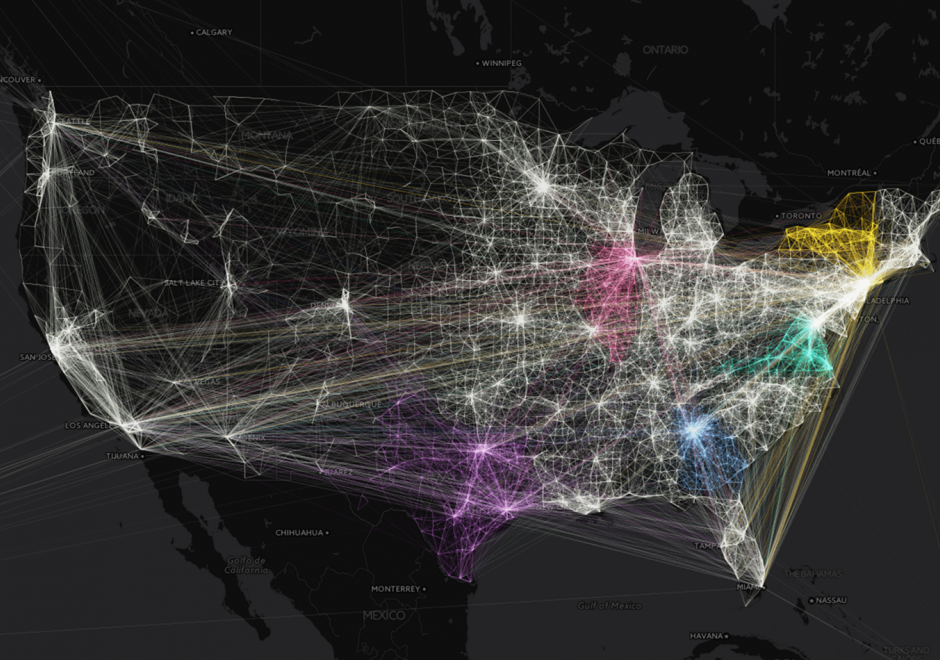

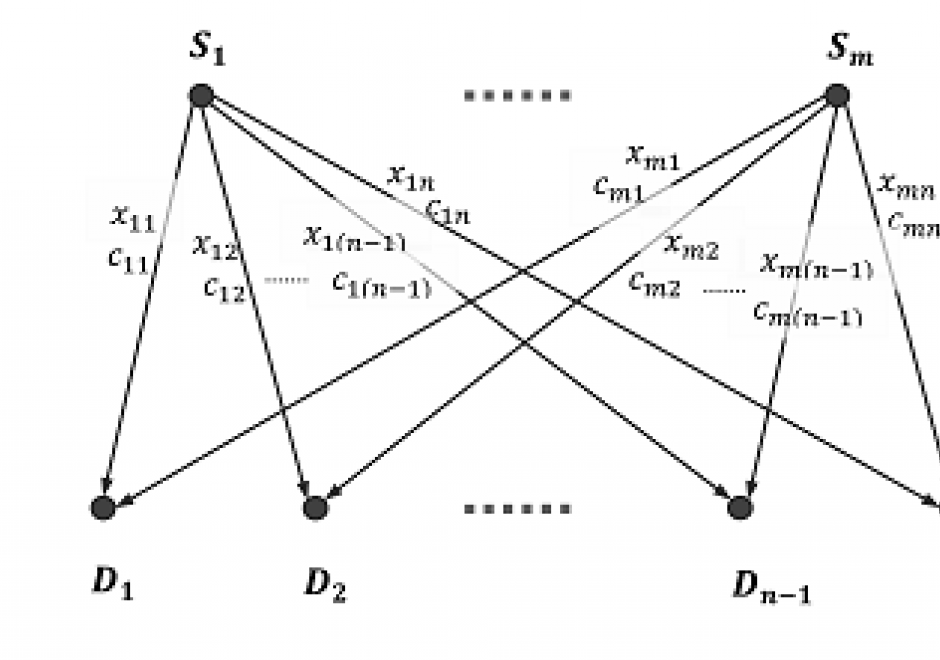

Regression analysis is a statistical technique commonly used in the social and physical sciences to model relationships between variables. To make unbiased, consistent, and efficient inferences about real-world relationships a researcher using regression analysis relies on a set of assumptions about the process generating the data used in the analysis and the errors produced by the model. Several of these assumptions are frequently violated when the real-world process generating the data used in the regression analysis is spatially structured, which creates dependence among the observations and spatial structure in the model errors. To avoid the confounding effects of spatial dependence, spatial autoregression models include spatial structures that specify the relationships between observations and their neighbors. These structures are most commonly specified using a weights matrix that can take many forms and be applied to different components of the spatial autoregressive model. Properly specified, including these structures in the regression analysis can account for the effects of spatial dependence on the estimates of the model and allow researchers to make reliable inferences. While spatial autoregressive models are commonly used in spatial econometric applications, they have wide applicability for modeling spatially dependent data.

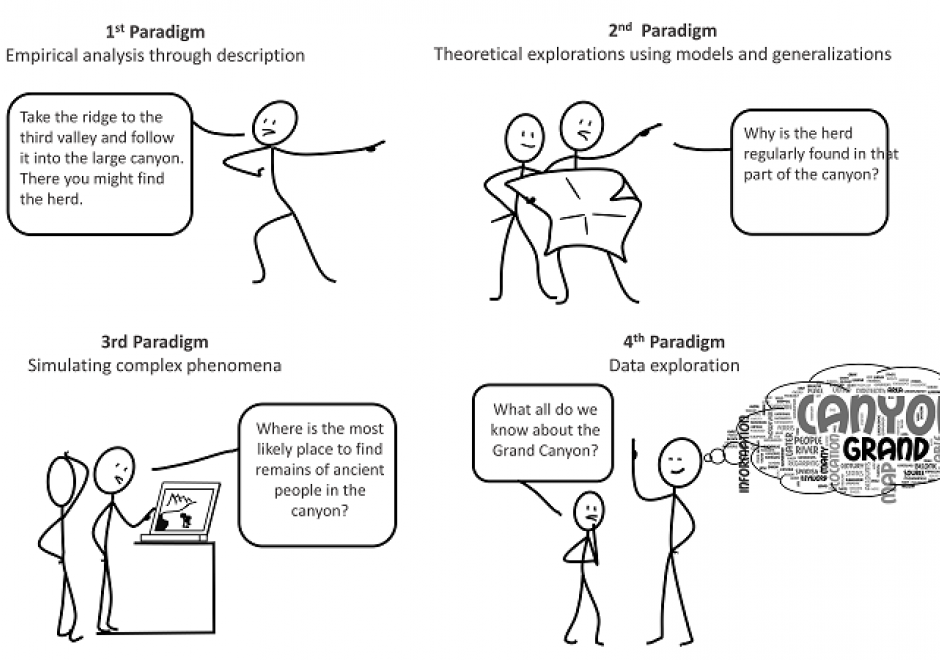

AM-84 - Simulation Modeling

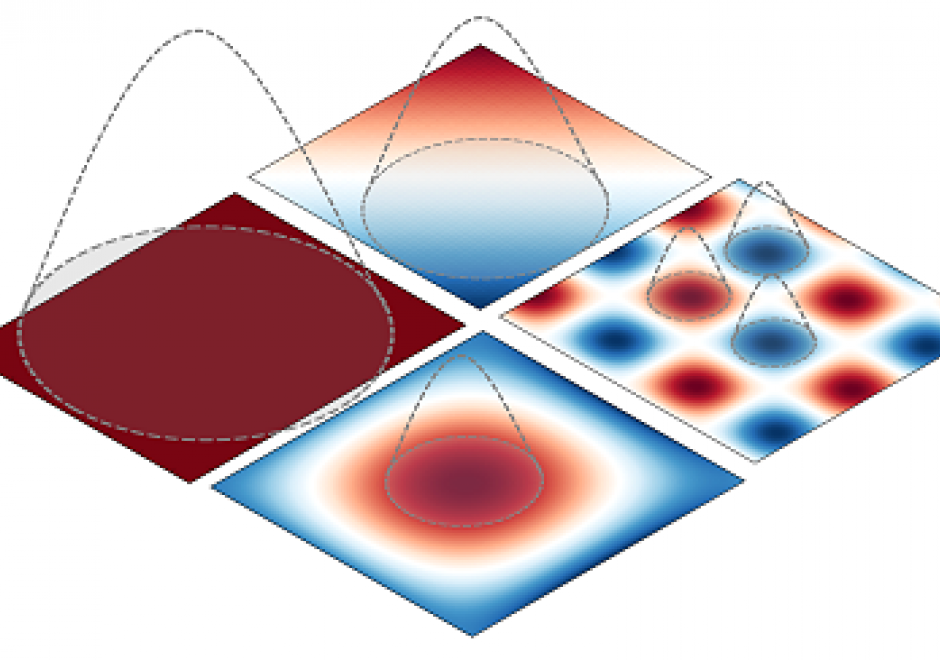

Advances in computational capacity have enabled dynamic simulation modeling to become increasingly widespread in scientific research. As opposed to conceptual or physical models, simulation models enable numerical experimentation with alternative parametric assumptions for a given model design. Numerous design choices are made in model development that involve continuous or discrete representations of time and space. Simulation modeling approaches include system dynamics, discrete event simulation, agent-based modeling, and multi-method modeling. The model development process involves a shift from qualitative design to quantitative analysis upon implementation of a model in a computer program or software platform. Upon implementation, model analysis is performed through rigorous experimentation to test how model structure produces simulated patterns of behavior over time and space. Validation of a model through correspondence of simulated results with observed behavior facilitates its use as an analytical tool for evaluating strategies and policies that would alter system behavior.