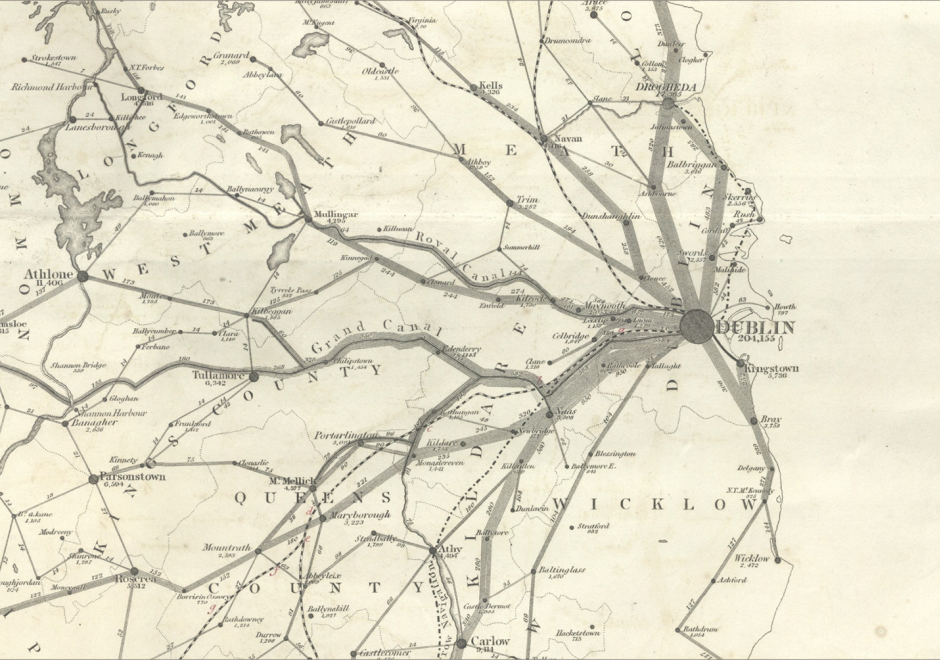

CV-31 - Flow Maps

Flow mapping is a cartographic method of representing movement of phenomena. Maps of this type often depict the vector movement of entities (imports and exports, people, information) between geographic areas, but the general method also encompasses a range of graphics illustrating networks (e.g., transit and communications grids) and dynamic systems (e.g., wind and water currents). Most flow maps typically use line symbols of varying widths, lengths, shapes, colors, or speeds (in the case of animated flow maps) to show the quality, direction, and magnitude of movements. Aesthetic considerations for flow maps are numerous and their production is often done manually without significant automation. Flow maps frequently use distorted underlying geography to accommodate the placement of flow paths, which are often dramatically smoothed/abstracted into visually pleasing curves or simply straight lines. In the extreme, such maps lack a geographic coordinate space and are more diagrammatic, as in Sankey diagrams, alluvial diagrams, slope graphs, and circle migration plots. Whatever their form, good flow maps should effectively visualize the relative magnitude and direction of movement or potential movement between a one or more origins and destinations.

GS-15 - Feminist Critiques of GIS

Feminist interactions with GIS started in the 1990s in the form of strong critiques against GIS inspired by feminist and postpositivist theories. Those critiques mainly highlighted a supposed epistemological dissonance between GIS and feminist scholarship. GIS was accused of being shaped by positivist and masculinist epistemologies, especially due to its emphasis on vision as the principal way of knowing. In addition, feminist critiques claimed that GIS was largely incompatible with positionality and reflexivity, two core concepts of feminist theory. Feminist critiques of GIS also discussed power issues embedded in GIS practices, including the predominance of men in the early days of the GIS industry and the development of GIS practices for the military and surveillance purposes.

At the beginning of the 21st century, feminist geographers reexamined those critiques and argued against an inherent epistemological incompatibility between GIS methods and feminist scholarship. They advocated for a reappropriation of GIS by feminist scholars in the form of critical feminist GIS practices. The critical GIS perspective promotes an unorthodox, reconstructed, and emancipatory set of GIS practices by critiquing dominant approaches of knowledge production, implementing GIS in critically informed progressive social research, and developing postpositivist techniques of GIS. Inspired by those debates, feminist scholars did reclaim GIS and effectively developed feminist GIS practices.