PD-14 - GIS and Parallel Programming

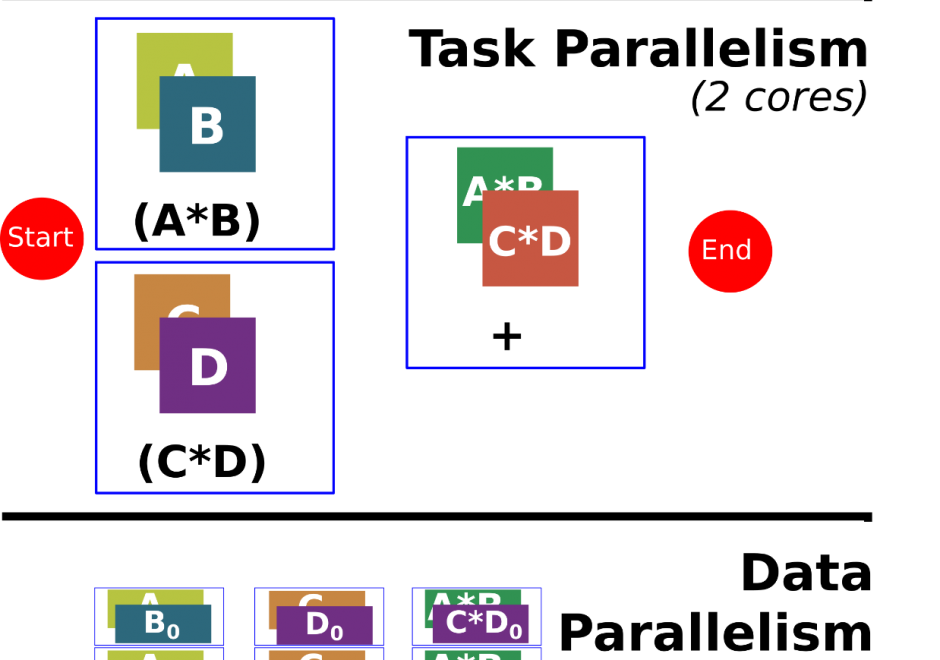

Programming is a sought after skill in GIS, but traditional programming (also called serial programming) only uses one processing core. Modern desktop computers, laptops, and even cellphones now have multiple processing cores, which can be used simultaneously to increase processing capabilities for a range of GIS applications. Parallel programming is a type of programming that involves using multiple processing cores simultaneously to solve a problem, which enables GIS applications to leverage more of the processing power on modern computing architectures ranging from desktop computers to supercomputers. Advanced parallel programming can leverage hundreds and thousands of cores on high-performance computing resources to process big spatial datasets or run complex spatial models.

Parallel programming is both a science and an art. While there are methods and principles that apply to parallel programming--when, how, and why certain methods are applied over others in a specific GIS application remains more of an art than a science. The following sections introduce the concept of parallel programming and discuss how to parallelize a spatial problem and measure parallel performance.

CP-27 - GIS and Computational Notebooks

Researchers and practitioners across many disciplines have recently adopted computational notebooks to develop, document, and share their scientific workflows—and the GIS community is no exception. This chapter introduces computational notebooks in the geographical context. It begins by explaining the computational paradigm and philosophy that underlie notebooks. Next it unpacks their architecture to illustrate a notebook user’s typical workflow. Then it discusses the main benefits notebooks offer GIS researchers and practitioners, including better integration with modern software, more natural access to new forms of data, and better alignment with the principles and benefits of open science. In this context, it identifies notebooks as the “glue” that binds together a broader ecosystem of open source packages and transferable platforms for computational geography. The chapter concludes with a brief illustration of using notebooks for a set of basic GIS operations. Compared to traditional desktop GIS, notebooks can make spatial analysis more nimble, extensible, and reproducible and have thus evolved into an important component of the geospatial science toolkit.